CHAPTER 6

Action in the North

Securing the Eastern Islands1

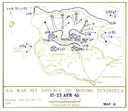

The rapid initial progress of Tenth Army had cleared the shore line of Chimu Wan and that of a large portion of the upper bay in Nakagusuku Wan by 5 April. Mine sweepers, operating under Admiral Blandy as Commander, Eastern Fire Support Group (CTG 51.1), were completing the dangerous job of sweeping the extensive reaches of both anchorages. Admiral Turner was anxious to make use of the eastern berths and beaches at the earliest possible moment. First, however, it was necessary to ascertain the Japanese strength on the six small islands that guarded the entrances to the anchorages. Major Jones’ FMF Reconnaissance Battalion was again tapped for the scouting mission. (See Map 12)

Since preliminary intelligence had indicated that Tsugen Shima was the only island defended in any strength, it was selected as the first target. The island’s size was not very significant, only 2,500 yards long by 1,200 yards wide, but its position southeast of Katchin Peninsula gave it effective control of the entrances to Nakagusuku Wan. The terrain of the island was generally flat, except in the south where a high ridge overlooked the village of Tsugen. Aerial reconnaissance had indicated that this ridge and the village below it were extensively developed strong points.

By midnight of 5 April the high-speed transports (APD’s) lifting Major Jones’ battalion were moving in toward the objective. The scouts embarked in rubber boats and made a landing on the northern coast of the island at 0200. Four civilians were encountered just inland from the landing point; two were captured, but the other two escaped, evidently alerting the garrison.2

Within minutes both assault companies3 began receiving machine-gun fire, Company A from the vicinity of Tsugen and Company B from a trench system in the northwest part of the island. Japanese mortars soon found the range of the landing party, and the battalion withdrew to the beach under a steady rain of shells. Since Major Jones’ assignment was to discover enemy opposition, not to engage it, he reembarked his unit at 0300. Despite Japanese claims of an easy victory over an “inferior” force,4 the battalion had accomplished its mission although it cost two men killed and eight wounded, all from Company A.

That evening the amphibious scouts began to investigate the remaining islands of the offshore group. At 0015, 7 April the entire battalion landed on Ike Shima, the northernmost

island. There was no sign of enemy troops or installations and only one aged civilian was discovered. Company B went on to Takabanare Shima, landing at 0530, 200 thoroughly cowed natives were the only inhabitants. At about the same time, two platoons of Company A made the trip to Heanza Shima and later, at 0800, used their rubber boats to cross over to nearby Hamahika Shima. Daylight reconnaissance confirmed the absence of Japanese soldiers, but added more than 1,500 civilians to the existing tally. These islands were later occupied by 3/5 in mid-April.5

After darkness had fallen on 7 April, Company B reembarked on its APD, circled Tsugen Shima, and made a landing on Kutaka Shima, opposite enemy-held Chinen Peninsula. A heavy surf capsized three of the boats as the company paddled in to shore and one man drowned. No enemy troops, installations, or civilians were found on the island and the Marines withdrew about 0100, 8 April.

While the reconnaissance battalion was searching the rest of the Eastern Islands on 7 April, swimmers of UDT 7 made a check of the proposed landing beach on the east coast of Tsugen Shima. They reported the water free of obstacles and the way clear for tracked vehicles to land. The UDT men spent the next two days looking over possible unloading beaches on Katchin Peninsula and the American-held portion of the Nakagusuku Wan shore line. While their tranport, the APD Hopping, was patrolling the entrance to the bay in the afternoon of 9 April, the hitherto silent garrison of Tsugen Shima opened up for a short period on the lightly-armed ship. Six hits were scored with 6-inch, 75mm, and 47mm shells, causing considerable structural damage, killing one and wounding 11 of the crew. In addition UDT 7 had one man killed and eight wounded by the enemy fire.

The guns that engaged the Hopping constituted the major armament of the Tsugen Shima defenders. A specially organized guard force with a strength of approximately 250 men, the garrison was built around the 1st Battery of the 7th Heavy Artillery Regiment. In addition to rifles, machine guns, knee mortars, and 81mm’s the unit was equipped with three 6-inch naval guns, two 75mm and two 47mm guns. All but one of these weapons were located in the major defensive position in the ridge southwest of Tsugen; one 6-inch gun was covered by the trench system in the north of the island.6

The capture of the Eastern Islands had been assigned to the 27th Infantry Division as its part of Phase I of the Tenth Army preferred plan.7 The information gained by the reconnaissance battalion on 6-7 April indicated that seizure of the islands did not warrant commitment of the entire division. Accordingly, General Buckner ordered General Griner to detach one regiment for the operation. At the same time, 8 April, in accordance with a request from General Hodge, the Tenth Army Commander directed the 27th Division to land on Okinawa and reinforce the XXIV Corps attack.

On 9 April as the main body of the 27th was coming ashore over the ORANGE beaches near Kadena, the ships of the 105th RCT (Colonel Walter S. Winn) were rendezvousing at Kerama Retto with Admiral Blandy’s command ship, the Estes. The admiral had been designated Commander, Eastern Islands Attack and Fire Support Group (TG 51.19).

In addition to the Estes, Blandy’s attack group consisted of the cruiser Pensacola, destroyersLaws and Paul Hamilton, three mortar gunboats, six control vessels, and four LST’s, one lifting LVT(A)’s of the 780th Amphibious Tank Battalion and three carrying LVT’s of the 534th Amphibious Tractor Battalion. The assault unit selected for the Tsugen Shima operation was the same one designated in the original comprehensive plan of the 27th Division to take the Eastern Islands–the 3d Battalion, 105th Infantry commanded by Major Charles DeGroff. The other two battalions of the 105th RCT were designated floating reserve for the operation, to be called up from Kerama if needed. The regimental commander in his headquarters ship, Rutland, would accompany the attack group to the target.

After the men of 3/105 had transferred to LST’s at Kerama, TG 51.19 left the anchorage, swung wide around Okinawa during the night,

Map 12

Reconnaissance and Capture of the Eastern Islands

6-11 April 1945

and came in on the target during the early morning hours of 10 April. Air and NGF had pounded Tsugen Shima intermittently since L-Day, especially after reconnaissance had developed the enemy defensive positions. On 10 April the support ships began firing at 0700, covering the area inland from the beach, the village of Tsugen, and its commanding ridge. At 0720, enemy mortars began returning the American NGF, reaching out for the LST’s which had incautiously approached beyond prescribed distance. LST 557 was hit, two crewmen were killed and one wounded before the landing ships withdrew to a safer area. Just before the scheduled landing at 0830, a strafing run by 12 carrier planes was made on the beach zone. Only one pass was completed, however, as closing weather made it necessary for the planes to return to base.

When naval gunfire support shifted inland, the armored amphibians crossed the line of departure, hitting the beach at 0839. Two minutes later the first assault LVT’s lumbered up out of the water and the men of 3/105 began advancing. Initial resistance was light, but the left flank company (Company I) soon became entangled in a day-long fire fight with enemy soldiers strongly entrenched in the stone and concrete rubble of Tsugen. Company L on the right, soon reinforced by the reserve company (K), swept through scattered opposition to secure the northern part of the island.

Hindered by a driving rain which served to conceal enemy strong points and curtail fire support capabilities, Company I made only limited advances during the day. As night fell, isolated enemy groups still held out in Tsugen and mortar fire from the heights above the village was causing a steady drain of casualties. Companies K and L, after securing the rest of the island, moved down into line with Company I to isolate the enemy holdouts.

With daylight on 11 April, Major DeGroff’s rifle companies attacked in a concerted effort to wipe out the garrison. Opposition was stubborn at first, but gradually died out. By 1530 organized resistance had been eliminated, and shortly thereafter the battalion was ordered to reembark.8Very few Japanese survived the violent battle and these only by virtue of 3/105’s early withdrawal. Enemy sources indicate that these survivors were able to rejoin the main body on Okinawa.9

In a day and a half’s fighting Major DeGroff’s battalion had lost 11 men, had 80 wounded in action, and three missing in action.10 An estimated 234 Japanese had been killed and all enemy installations destroyed; no prisoners were taken.

Having struck the 27th Division’s first blow in the battle for Okinawa, 3/105 rejoined its regiment at Kerama Retto during the night of 11-12 April. The battalion’s action had opened the approaches to Nakagusuku Wan, insuring adequate supply from the sea to both flanks of the XXIV Corps drive toward Shuri.

6th Marine Division Advances11

While the FMF Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion prepared the way for the seizure of the Eastern Islands, the 6th Marine Division moved into northern Okinawa with giant strides. Covering the rear of the division as it commenced its dash northward, the 7th Marines

Map 13

6th Marine Division

Progress in Northern Okinawa

L+4 thru L+27

in corps reserve patrolled the 6th Division zone south of the Nakadomari-Ishikawa line;12 the 6th Reconnaissance Company mopped up Japanese remnants from this boundary up the Ishikawa Isthmus to the line Yakada-Yaka; and, after being passed through by the 4th and 29th Marines on the morning of 6 April, the 22d Marines reverted to division reserve and commenced active patrolling back to the area of responsibility of the reconnaissance company.

Preceded by an armored spearhead and with patrols probing inland, the 29th Marines drove up the west coast in column of battalions and reached its objective at Chuda by noon. The 4th Marines, similarly deployed, moved up the east coastal road in a contact imminent formation, with 2/4 reinforced by a platoon of tanks as the advance guard.

Because of the few roads inland, Colonel Shapley’s plan was to move rapidly up the main road along the shore, detaching patrols from the advance guard to investigate to their source all roads and trails leading into the mountainous and generally uninhabited interior. In order to maintain control during the anticipated rapid advance, the regimental march CP moved out in a jeep convoy at the head of the main body.

By 1300, 2/4 had been used up by the detachment of small patrols and was relieved by 3/4 passing through. The 2d Battalion then reassembled at the rear of the column behind the 1st Battalion. The regiment halted in this formation at 1600 having advanced seven miles, despite the fact that three bridges destroyed by friendly air had restricted supply operations. (See Map 13)

The 4th resumed its advance the following morning with battalions disposed in the same manner as they had halted the previous evening. The day’s operations were virtually a repetition of those of 6 April. By noon the 3d Battalion had been dissipated by the commitment of security detachments to the flanks and the 1st Battalion passed through. Again opposition was limited to scattered stragglers,

BAILEY BRIDGE erected by 6th Division engineers over the ruins of a bridge blown by the enemy in an attempt to block the drive into northern Okinawa.

and the advance was retarded only by the condition of the road and enemy passive defense measures.

Japanese attempts to impede progress or destroy highway facilities during their retreat north were for the most part inept, and in very few instances was the forward movement of the 6th Division slowed to any great extent. Abatis, with neither mines nor booby traps attached or wired in place, were easily pushed aside by tank dozers and bulldozers. Mines in roads and defiles were not placed in depth and were not covered by infantry fire or protected by wire. In the main, mines constituted no more than a nuisance and caused very few casualties.13 Japanese demolitionists often failed to destroy bridges completely, and much time was saved in hasty construction by using the remaining structural members as foundations for new spans.

When the 6th Marine Division wheeled northward up the Ishikawa Isthmus, one company of the 6th Engineer Battalion was placed in direct support of each assault regiment. One platoon of the engineer company was attached to the advance guard. This platoon cleared road blocks, removed mines, and built hasty bypasses for combat vehicles around demolished

GRINNING TROOPS of the 29th Marines hitch a ride on a tank in their swift advance toward Motobu Peninsula.

bridges. The remainder of the company followed up repairing and replacing bridges and widening the narrow thoroughfares to accommodate two-way traffic wherever possible. In the wake of the assault regiments, the third engineer company of the division followed closely, further improving the roads and bridges.

The coastal roads narrowed as the mountains came down to the sea, requiring increased exertion on the part of the engineers to widen these trails.14 But despite these logistical difficulties and the fact that extensive patrolling through the rugged terrain was physically exhausting to the footsore infantry, another seven miles of enemy territory was penetrated by late afternoon when 1/4 reached the assigned objective just north of Ora. There, the 1st Battalion established a perimeter defense with the flanks secured on the coast. The regimental CP and Weapons Company set up in the village of Ora, while 3/4 and 2/4 established defensive perimeters at 1,000 yard intervals down the road.

On the western flank the 29th Marines had again seized its objective with little difficulty on 7 April. Advance armored reconnaissance elements reached Nago at noon, and by late afternoon the regiment had cleared the town and organized positions on its outskirts.

Behind the assault regiments, the 22d Marines in division reserve had been actively employed during the day seeking out and destroying bypassed pockets of enemy resistance. Ahead of the division the 6th Reconnaissance Company, its mop-up activities ended, sought to determine the nature of enemy resistance on Motobu Peninsula.

After scouting the bomb- and shell-flattened town of Nago, at noon on 7 April one platoon of the reconnaissance company, supported by tanks, swung up the west coast road to the village of Awa.15 At the same time, Major Walker led the remainder of his company and the tanks across the base of the peninsula to Nakaoshi. The patrol uncovered more enemy activity than had hitherto been revealed in the 6th Marine Division zone of action. The company met several enemy groups which were either destroyed or scattered.

Throughout the drive to the base of the Motobu Peninsula the 15th Marines was disposed with one battalion in direct support of each assault regiment and one in general support. Because of the rapidity of the advance, frequent displacements were necessary, averaging one a day for each battalion and regimental headquarters. The artillerymen were hard pressed to keep up with the fast moving infantry. But by stripping combat equipment to the bare minimum, substituting radio communications in place of wire, and leapfrogging units, at least one battalion of artillery was in direct support of each assault infantry regiment throughout the advance.16

To reinforce the fires of the divisional artillery, the 2d Provisional Field Artillery Group had been displaced to positions north of Nakadomari on the eve of the 6th Marine Division’s drive up the Ishikawa Isthmus.17 When resistance began to stiffen on the Motobu Peninsula, the 15th Marines was further augmented by the attachment of the 1st Armored

NAGO, objective of the 29th Marines’ advance in early April, as it looked after the end of the battle for Motobu Peninsula. (Army Photograph)

Amphibian Battalion on 8 April,18 and the following day the supporting corps artillery was moved forward to Besena Misaki at the southern extremity of Nago Wan, where it remained throughout Marine operations in the north.19

Because of the doubtful location of the enemy and a Tenth Army order to avoid destruction of civilian installations, unless there were clear indications or confirmation of the enemy’s presence, naval gunfire support was not extensively used during the drive to Motobu. However, after 5 April, all naval units supporting IIIAC were diverted to the 6th Division zone of action. These ships paced the advance up the coast firing up the numerous ravines leading down to the beach. One call fire ship was furnished each assault battalion during the day, and each regiment was furnished an illuminating ship at night.20

As the zone of reconnaissance was extended to the west on 8 April, there were clear indications, confirmed by aerial observation and photos, that the enemy had selected the rugged mountains of Motobu in which to make a stand. It was therefore necessary to reorient operations in order to reduce the Japanese garrison on the peninsula. Consequently, the 22d Marines was deployed across the island from Nakaoshi to Ora to cover the right and rear of the 29th Marines attacking to the west. The 4th Marines

assembled near Ora in position to support the 29th on Motobu or the 22d in the north.

For the next five days, while the 4th and 22d Marines combed the wild interior and patrolled to the north, the 29th Marines probed westward to develop the enemy defense.21 On 8 April, 2/29 moved across the base of the Motobu peninsula from Nago and occupied the village of Gagusuku.22 Initially in reserve, 1/29 was ordered to send one company to secure the village of Yamadadobaru. This mission was accomplished by Company C at 0900. An hour later the 1st Battalion was directed to Narashido to assist Company H of the 3d Battalion23 which had encountered stiff resistance.

Companies A and B moved out from Yofuke, just south of Nago, and at 1100 Company C set out from Yamadadobaru. At 1500 all companies converged on Narashido where heavy enemy machine-gun and rifle fire was encountered. Two hostile strong points were reduced, and the battalion dug in for the night.24

The following day saw the 29th Marines moving out in three columns to locate the enemy’s main force: the 3d Battalion along the south coast; the 2d Battalion along the north coast; and the 1st Battalion up the center of the peninsula. All columns encountered opposition which indicated that a considerable force confronted the division in the area from Itomi west to Toguchi.

On the left 3/29 found the roads rendered impassable by road blocks, mines, and demolitions.25In the center 1/29, ordered to occupy and defend Itomi, met stubborn resistance and was forced to dig in for the night 600 yards short of its objective. On the right 2/29 patrolled the north coast to the village of Nakasoni, destroying supply dumps and vehicles and dispersing small enemy groups.26 This battalion also scouted Yagachi Shima with negative results.

On 10 April, 2/29 seized Unten Ko where the Japanese had established a submarine and torpedo boat base. Large amounts of abandoned equipment and supplies were found, and civilians reported that some 150 naval personnel had fled inland to the mountains. On the other side of the peninsula 3/29 captured Toguchi and sent patrols into the interior, while 1/29 pushed forward through Itomi and uncovered well-prepared positions on the high ground north of the village.

During this period numerous contacts were made in the difficult terrain to the northwest and southwest of Itomi. Ambushes were frequent and enemy artillery fire increased in intensity. Night counterattacks were also stepped up. A particularly vicious attack, supported by artillery, mortars, machine guns, and 20mm dual-purpose cannon, struck the defensive perimeter of 1/29 on the night of 10-11 April.

On 11 April, patrols sent out by 2/29 to contact 1/29 near Itomi met with little opposition. This tended to confirm the estimate that the Japanese battle position was located in the

area between Itomi and Toguchi. Consequently, the 2d Battalion (less Company F) was ordered to discontinue operations on the north coast of the peninsula, move to the vicinity of Itomi, and establish defensive positions tied in with those of 1/29. Company F continued on patrol.27Reconnaissance detachments from 1/29 encountered only light resistance during the day,28 but 3/29, moving inland to gain contact with 1/29, ran into heavy resistance at Manna and was compelled to withdraw to Toguchi.29

In response to Admiral Turner’s expressed desire for the early capture of Bise Saki, in order to establish radar facilities there, General Shepherd ordered the 6th Reconnaissance Company to investigate the region on 12 April. If opposition was light, the area was to be seized and held pending reinforcement. This mission was successfully accomplished against scattered resistance.

Meanwhile, the 29th Marines continued probing in an effort to fix the hostile battle position. Patrols from 1/29 moving west encountered strong resistance from well-organized positions on the high ground south of the Itomi-Toguchi road.30 In the hills to the north of this road 2/29 also uncovered prepared positions.31 From the vicinity of Toguchi, 3/29 sent Company G north to contact the reconnaissance company and to meet Company F at Imadomari; Company H was ordered to effect a juncture with 1/29 at Manna; and Company I was to patrol the high ground to the southeast.

On the march toward Manna Company H, pinned down by intense mortar, light machine-gun, and sniper fire, was unable to continue without incurring unacceptable casualties. Company I moving to the southeast came under a galling fire from all directions early in the afternoon. Although materially aided by prompt call fires from the destroyer Preston, and covered by LVT(A) fire and an 81mm mortar barrage, Company I was extricated only with difficulty, suffering losses of eight killed and 33 wounded.32 By midafternoon Companies H and I had withdrawn into a perimeter defense at Toguchi, and the command post of 3/29 was receiving artillery and mortar fire.33

With this significant resistance developing in the zone of 3/29, Company G, upon its arrival at Imadomari at 1415, was immediately ordered back to Toguchi.34 At the same time, 3/22, which had been alerted during the morning after Company H had been hit,35 was ordered to assemble in division reserve at Awa. Battalion headquarters and two companies completed the movement by 1700 and the remaining company arrived at 0900 the following morning.36

The night of 12 April found the 6th Marine Division confronted with a fourfold task: to continue to occupy and defend the Bise area; to secure the line Kawada Wan-Shana Wan and prevent enemy movement through that area; to seize, occupy, and defend Hedo Misaki, the northernmost tip of Okinawa; and to destroy the enemy forces on the Motobu Peninsula.37

Company F of the 29th Marines was ordered to reinforce the 6th Reconnaissance Company at Bise.38 The 1st Battalion, 22d Marines had established a defensive perimeter at Shana Wan on 10 April. From this position 1/22 conducted vigorous patrolling to the north and eastward to the coast. By 12 April, patrols from 1/22 had contacted the 4th Marines on the east coast.39 The 3d Battalion, 4th Marines was ordered to move to Kawada on 13 April.40 The capture and defense of Hedo Misaki was assigned to 2/22, reinforced by Company A of the 6th Tank Battalion. The 2d Battalion, riding tanks and trucks, moved rapidly up the west coast on 13 April “beating down scattered and

ineffective resistance,” seized Hedo Misaki, and organized the defense of the area.41

Battle for Motobu Peninsula42

While the first three missions facing the 6th Marine Division were being fulfilled by extensive patrolling which met with little or no enemy interference, the fourth task, destruction of the Japanese garrison on Motobu, posed a more complicated problem.

The ill-fated Company I of the 29th had evidently discovered the bulk of the enemy force on the peninsula. This was further confirmed during the night of 12-13 April when some civilians, who had lived in Hawaii and spoke English, fell into the hands of the 29th Marines. These people reported a concentration of about 1,000 Japanese on the high ground south of the Manna-Toguchi road. They further stated that this force was commanded by a Colonel Udo, and contained an artillery unit of some 150 men under a Captain Hiruyama.43 Previous reports as to enemy strength and dispositions had been confirmed by the operations of strong combat patrols, and the hostile defenses were now firmly fixed in an area of some six by eight miles surrounding precipitous Mount Yae Take.

Around this towering 1,200 foot peak the Japanese had shrewdly selected and thoroughly organized the ground. The key terrain feature of the peninsula, the dominant heights of Yae Take commanded the outlying islands and all of Nago Wan. The steep and broken terrain precluded the use of armor and was of such an impassable nature that it also offered serious difficulties to the infantry. Moreover, the Japanese had obviously been organizing the ground over a considerable period of time. All likely avenues of approach into the position were heavily mined and covered by fire.

Intelligence indications placed enemy strength at 1,500 troops. This garrison, designated the Udo Force after its commander, was built around elements of the 44th IMB and included infantry, machine-gun units, light and medium artillery, Okinawan conscripts, and naval personnel from Unten Ko. In addition to 75mm and 150mm artillery, there were two 6-inch naval guns within the Japanese battle position which were capable of bearing on the coastal road for 10 miles south of Motobu, on Ie Shima, and all of Nago Wan.

The character of enemy resistance on Motobu made it apparent that the reduction of Yae Take was beyond the capabilities of a single reinforced regiment. Such being the case, the 4th Marines (less 3/4) was ordered to move from the east coast to Yofuke, just south of the juncture of the Motobu Peninsula and the main portion of the island. The 29th Marines was directed to continue developing the enemy positions on 13 April by vigorous patrolling and deploy for an early morning attack the following day.44

In compliance with General Shepherd’s orders, on 13 April, Colonel Victor F. Bleasdale again attempted to clear the Itomi-Toguchi road45 and link up his 1st and 3d Battalions. But Company A of 1/29, moving toward Manna, was ambushed and hit hard by fire from 20mm machine cannon. Patrols from 3/22, probing north from Awa, also came under fire and engaged in an hour-long fire fight before withdrawing under cover of 81mm mortars. During the afternoon the enemy placed artillery fire on this battalion’s positions.46

At the same time Japanese counterbattery fire was placed on the artillery positions of 2/15. This heavy bombardment inflicted 32 casualties, including two battery commanders and the executive officer of the third battery, and destroyed the ammunition dump and two

Map 14

6th Mar Div Advance on Motobu Peninsula

14 Apr 45

105mm howitzers.47 Air strikes were called in on the suspected hostile positions and patrols from 3/22 also tried to locate the enemy batteries;48 but as fires and exploding ammunition made the position untenable, 2/15 was forced to displace to alternate positions.49

Meanwhile, the 4th Marines (less 3/4) had moved on foot across the island to Yofuke. There, the leading battalion (2/4) was directed to continue on to a point on the southwest corner of the peninsula just below Toguchi. The 2d Battalion reached this area at 1700, after a difficult march of over 18 miles. At 1630, while digging in at Yofuke, the 1st Battalion was similarly ordered to a position just west of Awa. This move was accomplished before dark by shuttling a company at a time by truck. Thus, nightfall found the 4th Marines disposed with the 1st and 2d Battalions in separate perimeter defenses three miles apart on the southwest coast of Motobu, the 3d Battalion 20 miles away on the east coast of Okinawa, and the regimental headquarters set up with the Weapons Company at Yofuke.50

A coordinated attack was planned for 14 April, which contemplated reduction of the enemy center of resistance by action from two opposing directions. The 4th Marines, with 3/29 attached, were to attack inland in an easterly direction while the 29th Marines drove west and southwest from the center of the peninsula. Although the high Yae Take hill mass intervening between the two assault regiments left little chance of overlapping supporting fires, implementation of this rare scheme of maneuver nevertheless required careful coordination of artillery, air, and naval gunfire. (See Map 14)

In Colonel Shapley’s zone of action, the 4th Marines was ordered to seize initially a 700-foot ridge some 1,200 yards inland from the coast. This high ground dominated the western coastal road, and it was immediately behind it that Company I of 3/29 had been ambushed, cut off, and badly mauled on 12 April. Subsequently,

MAJOR GENERAL LEMUEL C. SHEPHERD, JR., Commanding General, 6th Marine Division at Okinawa.

sporadic machine-gun fire had also been received from that area.

Early on the morning of 14 April, a security patrol from 1/4, in regimental reserve, was fired on, and eight casualties were inflicted on the Marines before the Japanese were driven back.51 But the attack jumped off according to plan at 0800. From the vicinity of Toguchi, 3/29 attacked with two companies, G and H, in assault. On the right of 3/29, 2/4 moved out in a similar formation with Companies G and E in assault. Preceded by an intense artillery, aerial, and naval bombardment, the Marines advanced against surprisingly light resistance. Challenged only by scattered mortar and light artillery fire, both battalions were on the objective before noon,52 with the left flank of 3/29 anchored on a very steep slope.

In order to protect the open right flank, the regimental reserve (1/4) moved up the coast during the morning to an assembly area to the right rear of 2/4. At 1100, Company C of the 1st Battalion was ordered to seize a commanding

ridge to the right front of the 2d Battalion. Company C made contact with small groups of the enemy by noon, and soon thereafter began receiving mortar and machine-gun fire. Company A was committed on the left of Company C and the advance continued.53

Concurrently, the attack was resumed by 2/4 and 3/29 to seize the next high ground: another ridge 1,000 yards to the front. To cover the advance, heavy naval gunfire and artillery barrages were again laid down and two air strikes were called in.54 But as the assault echelons moved into the low ground on the way to the next objective, enemy resistance began to stiffen appreciably. The broken terrain, covered with scrub conifers and tangled underbrush, was ideally suited to defense, and the Japanese exploited this advantage to the utmost.

Initial opposition consisted of small enemy groups. These hostile covering forces employed every available means to delay and disorganize the advance, and to mislead the attackers as to the location of the battle position. The Japanese would lie in concealment, with weapons zeroed in on a portion of a trail, allowing a considerable number of Marines to pass before opening up on a choice target. An entire platoon was permitted to pass a point on a trail without interference, but when the company commander reached that point with his headquarters section, a burst of machine-gun fire killed him and several others. Officer casualties were excessively high. In an area in which there had been no firing for over half an hour, Major Bernard W. Green, commanding 1/4, was killed instantly by machine-gun fire. No one else was hurt, although Major Green was standing with his operations and intelligence officers on either side of him. Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, Regimental Executive Officer, assumed command of the battalion.

“It was like fighting a phantom enemy.”55 For while the hills and ravines were apparently swarming with Japanese, it was difficult to close with them. The small enemy groups, usually built around a heavy Hotchkiss machine gun augmented by Nambus, would frequently change positions in the dense vegetation. Hostile volleys elicited furious Marine fusillades into the area from whence the firing had come. But after laboriously working their way to the spot, the Marines came upon only an occasional bloodstain on the ground. Neither live nor dead Japanese were to be found. One Marine registered his impression of these tactics by blurting out, “Jeez, they’ve all got Nambus, but where are they?”56

The first strong enemy contact was made at 1350, when Company G of 2/4 came under rifle, machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire. Within five minutes Company E met similar resistance. The artillery piece was spotted and silenced by naval gunfire and artillery which were brought to bear on it.57

A considerable number of casualties having been inflicted on Company G, Company F (less one platoon in battalion reserve) was committed to its support; and despite their stubborn delaying action, the enemy covering forces were steadily driven in, and 2/4 took the ridge to its front by a combined frontal attack and envelopment from the right.58

By 1630, 3/29 and 2/4 were digging in on the regimental objective, with 2/4 in contact with 1/4 which held the high ground on the right. During the day’s advance Company B had been committed on the right of Company C. The Regimental Weapons Company, denied effective use of its heavy weapons by the terrain, was organized as a rifle company to patrol the open right flank of Company B.

During the day 3/4 moved across the island by motor march and relieved 3/22 in division reserve, 3/22 returning to its patrol base at Majiya. Upon arrival at Awa, Company K of 3/4 was sent on a patrol mission along the south and west coasts of the peninsula to Bise. There Company K relieved Company F of 2/29 which returned to parent control on 15 April.59

Map 15

6th Mar Div Advance on Motobu Peninsula

15-16 Apr 45

While the 4th Marines attacked to the east, the 29th Marines moved out from Itomi to the west in a column of battalions to eliminate the strong positions which had been located by patrols during the previous four days60 and clear the Itomi-Toguchi Road. But as the attack developed, it became clear that an advance in a westerly direction would be difficult and costly. Consequently, the attack was reoriented to proceed initially in a southwesterly direction in order to take advantage of the high ground.

With 1/29 leading, the advance progressed 800 yards up steep slopes against determined resistance.61 Late in the afternoon the 1st Battalion was pinned down by heavy enemy fire from the high ground to its front. The 2d Battalion was committed on the left flank and the troops were ordered to dig in for the night.

On 15 April, Colonel William J. Whaling assumed command of the 29th Marines from Colonel Bleasdale, and the regimental CP moved to Itomi.62 During the day the regiment consolidated its positions on commanding ground and maintained constant pressure on the rear of the Yae Take position by vigorous patrolling to the west and northwest.

On the other side of the Yae Take massif, the attack of the 4th Marines jumped off at 070063 in the same formation in which it had halted for the night. Initially, small, scattered groups opposed the advance in a manner similar to that which had prevailed the previous day; but by noon, halfway to the objective, resistance sharply increased. From caves and pillboxes sited in dominating terrain, the enemy laid down heavy and effective fires on the assault units as they climbed the steep mountainside. (See Map 15)

Engaging in numerous fire fights, 3/29 pushed forward to the east and south some 900 yards through intense machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire.64 But the advance was held up by an enemy strong point on Hill 210, 500 yards to the right front. Besides well-dug-in machine guns and mortars, this position also contained the cave-dwelling mountain gun located the day before. Despite the continued attempts of naval gunfire and artillery, and supporting air using 500-pound bombs and napalm to destroy it, this piece continued to function and do considerable damage with direct observed fire.

Fighting was extremely bitter all along the line, 2/4 again having tough going, as did 1/4 in its efforts to capture the high ground which dominated the right flank. Advancing with three companies abreast (less one platoon of Company E in battalion reserve), 2/4 came under fire at the outset of the attack. But after a day’s hard fighting, Companies E and F seized Hill 200.

Company G, however, experienced the greatest difficulty. Five minutes after jumping off, this company came under heavy enemy fire which continued throughout the day. The battalion reserve was committed to support the attack, and Company G despite severe casualties (65 including three company commanders) eventually advanced three-fourths of the way up the hill just to the right of Hill 200, from whence it withdrew to a more suitable defensive position and tied in with Company F. On the right a 200-yard gap remained between 2/4 and 1/4 which was covered by fire. During the late afternoon 1/4 finally secured a key hill mass immediately southwest of Yae Take, from which it had been driven back earlier in the day.

The attack ceased at 1630 with the two battalions of the 4th Marines on the objective and 3/29 digging in on favorable ground slightly short of it. During the day the supply situation had become more acute, casualties had mounted, and the troops were very tired. But numerous caves had been sealed and 1,120 enemy dead counted. The handwriting was on the wall for Colonel Udo. That night he decided to shift to guerrilla operations, moving his command to the mountain fastnesses of northern Okinawa by way of Itomi.65

TOGUCHI and the first line of hills guarding the approaches to Mount Yae Take under naval bombardment on L-Day. In the right background is Sesoko Shima. (Navy Photograph)

By this time it was obvious that the 4th Marines was confronted by a force of at least two companies that had organized the difficult terrain to the best possible advantage. Moreover, it was apparent that the direction of attack was that which the Japanese had anticipated and for which they had prepared their defenses. Coupled with the fact that the advance was still toward friendly troops and artillery, these factors led to the decision to contain and envelop the strong point by flanking action from the right, shifting the direction of the main effort from east to north.

In view of these developments, 3/4 reverted to regimental control for the operations of 16 April, and 1/22 was ordered into division reserve at Awa.66

On 16 April the 6th Marine Division was oriented to launch a full scale attack on the enemy from three sides. The 29th Marines would continue to drive in from the east. The 4th Marines with 3/29 attached were to attack from the west and southwest. Strong combat patrols from 1/22 were to strike north into the gap between the 4th and 29th and effect a juncture between the two regiments.

Each of these three principal infantry elements was assigned a battalion of artillery in direct support. The artillery was so employed that the fires of two battalions of the 15th Marines, one company of the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, and a battery of the 7th 155mm Gun Battalion could be placed in any of the three zones of action.67

In the zone of the 4th Marines, the scheme of maneuver called for 3/29 to seize the high ground 500 yards to its front, which included the formidable Hill 210. On the right of this

battalion, 2/4 was to maintain its position and support by fire both the attack of 3/29 and that of 1/4 which was to swing its right flank to the north. Moving from its assembly area at 0700, 3/4 was to take the most direct route to its place on the division objective and tie in with 1/4. Inasmuch as 1/22 would not start from Majiya until first light,68 the Weapons Company of the 4th Marines, was ordered to patrol thoroughly the area to the right rear of 1/4 and 3/4.

When the attack resumed at 0900, having been delayed by supply difficulties,69 Company H on the right flank of 3/29 faced Hill 210 frontally. Consequently Company G in the center was ordered to break contact with Company I on its left and assault the flank of the stubborn strong point from the south. Company H was to move its support platoon into the gap left by Company G, and support that company by fire, as was 2/4 from the lofty heights of its position on the right.

The success of an envelopment is largely dependent on the ability of the secondary attack to contain the bulk of the enemy forces, and in this case the supporting fires effectively kept the defenders down until Company G had seized the top of the hill and swarmed over the forward slope. Blasted from their caves with grenades and demolitions, the demoralized Japanese hastily retreated, effectively pursued by fire from both assaulting and supporting units.

By 1200, 3/29 had captured its objective. The ubiquitous mountain gun had been silenced and 147 enemy dead counted. The positions of Companies H and G were inverted, with Company H in the center of the line and Company G on the right flank firmly holding Hill 210.

At the same time that 3/29 had secured its objective, 1/4 had completed its pivoting movement to the north, and had established contact with 3/4. This change in direction was accomplished by Company A, supported by fire from Company C, seizing a ridge directly below Mt. Yae Take, while Company B was sent to take the high ground on the right and remain in position until relieved by 3/4.70 Well to the rear, 1/22 had begun its advance to cover the open flank of the 4th Marines.

Thus, at noon, 3/29 and 2/4 were solidly entrenched on high ground looking to the east, while the front of 1/4 and 3/4 formed a right angle to their positions, facing north. When the attack again jumped off, 3/29 and 2/4 remained in position to support by fire the advance of 1/4 and 3/4.

At 1230 the attack was resumed with the redoubtable Mt. Yae Take lying in the zone of 1/4. The 1st Battalion moved out with Company A on the left attacking frontally up the nose of the hill mass and Company C working up a draw to its right seeking an opportunity to envelop.

While progress up the steep slope was naturally slow, only light and scattered small-arms fire was encountered initially. But as Company A reached the summit, it was met with a withering fire at very close range. In the face of intense small-arms, grenade, and knee mortar fire the Marines withdrew below the crest and answered in kind with grenades and 60mm mortars. The fighting was close and fierce; the hilltop was untenable to either side until murderous fire laid down by 2/4 against the reverse (north) slope and effective artillery support enabled Companies A and C to push the assault home–this time to stay.

Although Companies A and C were in possession of Yae Take, the situation was nevertheless critical. The two companies had sustained over 50 casualties, and their ammunition was nearly exhausted. Moreover, the remaining enemy in the area were apparently gathering their strength for a counterattack. But

the effective artillery fire of the 15th Marines and the excellent supporting mortar and machine-gun fire of the 2d Battalion from its position in rear of the hostile strong point, held the Japanese in check until ammunition could be brought up.

Of this phase of the capture of Yae Take, the operations officer of the 4th Marines observed that:

If the supply problem was difficult before, it was a killer now. That 1,200-foot hill looked like Pike’s Peak to the tired, sweaty men who started packing up ammunition and water on their backs. Practically everyone in the 1st Bn headquarters company grabbed as much ammunition as he could carry. A man would walk by carrying a five-gallon water can on his shoulder and the battalion commander would throw a couple of bandoleers of ammunition over the other! . . . The battalion commander, on his way up to the front lines to get a closer look at the situation, packed a water can on his way up. Stretchers also had to be carried up, and all hands coming down the hill were employed as stretcher bearers.71

The 1st Battalion received additional assistance in resupply and evacuation in the late afternoon, when men of Company K coming up from the rear to return to control of 3/4 aided in taking out the wounded of 1/4, and on their return trip carried in water and ammunition.72

Although 1/4 was resupplied with ammunition as quickly as possible, it was none too soon. At 1830, an hour after the capture of Yae Take, the enemy reacted with a fanatical Banzai charge against the 1st Battalion’s front. An estimated 75 Japanese launched a strong attack, but with the help of the supporting fires of the artillery and 2/4, this force was virtually annihilated. By dark, Mt. Yae Take, dominating the entire area, was held securely.

During the afternoon 3/4 secured its objective against scattered small-arms and mortar fire, but met no organized resistance in any great strength. On the left, it was tied in with 1/4, Lieutenant Colonel Beans having committed Company B to establish contact. On the right, 1/22, retarded more by the terrain than the small enemy pockets of resistance which it had encountered and reduced, was unable to gain contact with the 4th or 29th and dug in an all-around defense for the night.73

While the 4th Marines was storming the fortified position on Mt. Yae Take, the 29th maintained relentless pressure against its rear. The opposition which faced the 29th was similar to that on the front of the 4th. From log-reveted bunkers and occasional concrete emplacements the enemy resisted the advance with increasing stubbornness, supported by machine guns, mortars, and artillery concealed in ravines and in caves on the high ground.74 Rugged terrain and an acute supply situation also contributed to the difficulties confronting the 29th Marines in accomplishing its task of clearing the high ground flanking the Itomi-Toguchi Road.

The enemy displayed his usual ability to exploit the terrain and derived the maximum benefit from his weapons emplaced in caves and pits and concealed by natural cover. Particularly noteworthy was his use of 20mm dual-purpose cannon against personnel. Fire from these weapons on battalion CP’s was a daily occurrence. All roads and natural avenues of approach were covered. Any attempt to move over the easier routes was met with bitter and effective resistance.

Consequently, “the method of reducing the enemy positions followed a pattern of ‘ridgehopping’,”75 covered by the fires of all supporting weapons. This tactic enabled the attacker to envelop the hostile defenses and reduce them in detail. Numerous abandoned positions and weapons encountered by the 29th indicated that the determination of the Japanese to resist diminished considerably when they were taken from the flank. In contrast to a coordinated advance with all units in contact across a broad front, the action in the zone of the 29th Marines was characterized by attacks that, even when delivered simultaneously, constituted a series of local patrol actions to seize critical positions, followed by mopping up activity within the area.

Throughout the advance westward from Itomi artillery and naval gunfire support had been habitually employed, but a particularly

Map 16

6th Mar Div Advance on Motobu Peninsula

17-23 Apr 45

heavy preparation was laid down on the morning of 17 April prior to resumption of the attack. At 0800 the 29th Marines advanced to effect a juncture with the 4th Marines along the Itomi-Toguchi Road. On the right, 1/29 moved out against light resistance, but over difficult terrain that made progress slow.76 However, by 1300 the battalion had secured its objective, the highest hill in its area.77 (See Map 16,)

The hostile positions confronting 1/29 were on the crest and face of the hill and presented a most difficult target for the USS Tennessee, in support, whose line of fire was almost parallel to the slope. Yet the intense bombardment delivered by the main and secondary batteries of this ship, together with the rapidity of the troops’ advance,78 was largely responsible for the capture of the hill without casualties. The Marines killed eight Japanese on the way up and 32 on the top; but the huge craters created by the Tennessee contained the bodies of more than 100 enemy dead.79

An hour after resuming the attack, 2/29 on the left flushed some 50 of the enemy, who fled to the northwest.80 Thereafter, the 2d Battalion advanced steadily against sporadic resistance and destroyed a considerable amount of enemy equipment, ammunition, and supplies.81 Before noon physical contact had been made with 1/2282 which had reduced the positions met in its zone and captured large quantities of clothing and ammunition. After contacting the 4th Marines on the left, 1/22 was pinched out of the line and withdrawn to the vicinity of Awa.83

Because of the critical supply situation, the 4th Marines did not launch its attack until

ASSAULT TROOPS of the 4th Marines probe the hills of the peninsula after the capture of Mount Yae Take.

1200 on 17 April. At that time the 1st and 3d Battalions on the right of the regiment resumed the advance toward the regimental objective on the Itomi-Toguchi Road. The front of the two battalions on the left, 2/4 and 3/29, faced east at right angles to that of the assault units. They were therefore ordered to remain in place and support the assault battalions from present position until their fires were masked by the advance of 1/4 and 3/4.

The progress of the attacking echelon was rapid, being down hill all the way and impeded only by scattered stragglers. Elaborate fortifications, intricate communications systems, and several bivouac areas were overrun. The area was strewn with enemy dead and military impedimenta. Large quantities of equipment, weapons, food, and clothing were uncovered and either captured or destroyed. Sweeping across the front of 3/29, 1/4 found two 8-inch naval guns, five artillery pieces, eight caves full of ammunition, and over 300 dead Japanese in front of the position of Company G on Hill 210.84 The 1st Battalion met only

one or two of the enemy, while the 3d Battalion killed 56 during the day without losing a man.85

As the axis of the attack of the 4th and 29th Marines gradually shifted to the northward, the desired juncture was effected between the two units, and 2/29 was withdrawn from the line to clear out any bypassed pockets of resistance remaining in the regimental zone.86 The day’s operations had revealed strong indications that the enemy was no longer able to maintain his position, that he was endeavoring to escape by retreat, and that the 6th Marine Division had broken the back of the Japanese defenses in the area. This estimate was confirmed when the 4th Marines captured an enemy map which showed the Yae Take position as the only organized resistance on Motobu.

Late afternoon saw the 4th and 29th Marines along the high ground overlooking the Itomi-Toguchi Road. Companies H and I of 3/29 were moved abreast of 1/4 and extended to the left around Toguchi, and Company G remained in a perimeter defense on Hill 210.87 On the opposite flank 2/29, after mopping up, set up a battalion strong point on the high ground north of Itomi.88

After four days of vigorous combat, activity in the Motobu area on 18 April was confined to reorganization, consolidating the previous day’s gains, patrolling the Itomi-Toguchi Road, and resupply. The now bypassed 3d Battalion of the 29th was detached from the 4th and moved around the base of the peninsula by truck to rejoin its parent unit at Itomi. Similarly, 1/22 returned to Majiya by motor march.89 In the 4th Marines’ area 1/4 went into reserve, bivouacking near Manna.90

Upon the return of 3/29 to regimental control, that unit was committed to a position on the right flank, north of Itomi, to block enemy escape routes to the east. The left of the 29th pushed northward to straighten out the lines with the 4th.91 While 3/4 conducted local patrols, 2/4 thoroughly patrolled the area over which 1/4 and 3/4 had passed the previous day. Besides the presence of mines in the roads throughout the area, the enemy had lacerated the Itomi-Toguchi Road with six tank traps which greatly hindered supply.

The final drive to the north coast began on 19 April, with the 4th and 29th Marines abreast. Colonel Shapley passed 2/4 through 3/492 and the regiment moved north with the former on the right. Colonel Whaling committed 2/29 on the right of 3/2993 and the regiment pushed forward on a three battalion front with 1/29 in contact with the 4th Marines. Elaborate systems of caves and trenches were encountered, the trenches littered with many enemy dead, presumably the victims of artillery, naval gunfire, and air. Resistance from stragglers was negligible, and the 4th and 29th Marines reached the north coast on 20 April, having eliminated all organized resistance on the Motobu Peninsula.94

At the conclusion of the battle for Motobu, the 6th Marine Division had lost 207 killed, 757 wounded, and six missing in action. Over 2,000 Japanese troops were counted who had given their lives defending their positions with characteristic tenacity. Garrison and patrol sectors were assigned the units on Motobu,95 and mopping up operations continued throughout the zone of the III Amphibious Corps.96

Marines’ “Guerrilla War”97

Colonel Udo’s formidable Yae Take redoubt constituted the only significant organized resistance encountered by III Amphibious Corps during the month of April. But countering the activities of the ubiquitous guerrilla remained a continuing task in General Geiger’s area of responsibility throughout the period. Independent or semi-independent groups of irregulars, employing tactics based on a small force

striking a sudden blow against isolated detachments or convoys, attempted to harass, delay, and wear down the invaders.

In general, the scope and intensity of partisan operations increased progressively as the advance moved northward. The primitive wilderness of the north offered irregular troops the opportunity to exploit to the maximum the sources of information within the civil population, their thorough knowledge of the difficult terrain, and the lack of roads. At the same time, under these conditions, regular forces of superior strength and armament operating against guerrillas are often hindered by a lack of reliable information, dependence on an organized supply system, and difficulty in bringing the partisans to a decisive engagement.

In the southernmost portion of the IIIAC area, aside from picking off occasional stragglers, the principal activities of the 5th Marines were confined to improvement of the road net, sealing burial vaults, and demolishing the myriad caves. But to the north, as elements of the fast moving 6th Division neared the Motobu Peninsula and its lines of communication extended, positive guerrilla action emerged. During the night of 8-9 April a marauding party of undetermined strength, broke into the IIIAC Artillery area near Onna and destroyed a trailer and a small power plant. This was followed at dawn by an attempt to disrupt traffic through Onna, when other enemy groups rolled crudely made demolition charges from the bluffs along the road north and south of the village as vehicles passed.98

At 1000, on 9 April the 6th Marine Division rear boundary was established along the Chuda-Madaira road, and the northern boundary of the 1st Marine Division along the Nakadomori-Ishikawa line. The task of patrolling the region between division boundaries fell to the 7th Marines (less 3/7) in corps reserve at Ishikawa.99 Consequently, 1/7 was moved to Chimu to cover the northern half of the regimental zone of responsibility while 2/7 and certain regimental troops remained in a perimeter defense around the rubble of battered Ishikawa with the collateral mission of patrolling the rugged terrain north and inland from the village.100

In the main, the defense of Ishikawa consisted of frustrating the night infiltration efforts of Japanese and Okinawan irregulars in search of food. These enemy groups, which rarely exceeded a half dozen men, occasionally probed the lines for safe routes of entrance. More often they moved through the gaps in the perimeter individually or in pairs; but most of them were killed or wounded either entering the village or leaving it. Initially, patrols combed the spinous heights of the narrow waist of the island without incident. But as pressure on the main Japanese forces in northern Okinawa increased, the “eerie feeling that Okinawa was a theater in which the enemy was not present, or in which he was a mysterious wraith”101 was suddenly dispelled for the 7th Marines, when a combat patrol of 2/7 encountered a well laid ambush on Ishikawa Take–the highest elevation on the isthmus.

On 12 April, Company E moved into this difficult terrain, which had previously been patrolled by Companies G and F with negative results. Upon entering a saddle near the Ishikawa summit the leading platoon was ambushed, and the entire company soon was pinned down on the narrow trail102 by heavy mortar, machine-gun, and rifle fire from an enemy force entrenched on the high ground, and estimated to be 100 to 150 troops.103

Inasmuch as at least a day would be required to attempt an envelopment through the rugged terrain, the Marines had no alternative but to withdraw. By the time Company E had fought its way out of the trap, under cover of indirect supporting fire from self-propelled 105mm howitzers of the Regimental Weapons Company, five Marines had been killed and 30 wounded.

The following day Lieutenant Colonel Berger closed in on the area with two companies. Company E was ordered to occupy the high ground

south of the saddle, and Company F was directed to move to a similar elevation on the other side. Advancing against token resistance, which nevertheless inflicted some casualties, both companies seized and occupied their objectives. The elusive enemy, however, had vanished into the tangled maze of ridge spines, deep gorges, and thickets of scrub pine and bamboo.

After an uneventful night on the twin peaks, the two companies were once more withdrawn in order to approach the infested area from a new direction. Upon their retirement, however, the enemy reappeared on the high ground to pursue by fire and inflicted a number of casualties on the Marines.104 The two companies circled to the far side of the island, consolidated their lines, and moved in from the west on the enemy pocket which was well concealed on commanding ground. On 14 April 2/7 pinned down the Japanese, who did “not appear to be well organized,”105and ferreted them out by patrol action.

But at best, it was painstaking and time consuming business. The western slopes of Ishikawa Take were the least precipitous, but the lush vegetation there seriously hampered effective patrol action. Since the dense growth of bamboo and scrub conifers frequently limited visibility to three to five feet off the trails and precluded the use of flank patrols, war dogs proved a valuable asset.106 To alleviate supply difficulties engendered by the configuration of the terrain and the lack of roads, the ban on the use of captured native horses (even for military purposes) which had hitherto prevailed was lifted and pack trains were organized to supply 2/7 while it operated in this isolated region. Resistance in the area continued until 23 April, and 2/7 accounted for about 110 enemy dead during the period.107

On the fringe of the pitched battle on Motobu, the tempo of partisan warfare increased as the fight for Yae Take threatened the destruction of the main Japanese forces in the Marines’ area. Every afternoon at dusk, as the infantry was digging in, the enemy regularly harassed artillery positions, and in consequence delayed registration of night defensive fires.108 When the 1st Battalion, 15th Marines, in direct support of the 22d, displaced to the vicinity of Taira on 12 April to cover the advance to the northern tip of Okinawa, forays against its perimeter occurred almost nightly. In addition to sporadic sniping and knee mortar fire, the ill-armed Boeitai threw grenades, demolition charges, and even antipersonnel land mines into installations on the rim of the battalion area. The hostile forces enjoyed excellent observation from the hills in rear of the area, and attacks against 1/15 were apparently coordinated. Charges were thrown near the fire direction center; a tractor was hit by rifle fire; and an enemy infiltrator, armed with demolition charges, was killed near an ammunition dump.109

From 14 through 16 April, at the climax of the battle on Yae Take, fires broke out in various villages along the west coast from the southern extremity of Nago Wan to the northernmost point of the island. At daybreak on 17 April, hostile raiders swept down on Nakaoshi, and simultaneously struck the water point and supply installations at the 6th Engineer Battalion CP nearby. In connection with these events, there were strong indications of civilian collaboration with the Japanese military forces. Investigation of the series of fires on the west coast revealed evidence of sabotage on the part of the natives. In the case of the dawn attack on Nakaoshi, the villagers left the settlement just before the onslaught, and fires in the buildings started shortly thereafter.

The security threat existing within the local populace, also appeared in the zone of the 1st Marine Division. On 9 April, 3/5 reported that many civilians seemed to be destroying their passes and staying out during the hours of darkness; and that there was “no reason to believe they [did] not contact the Nips at night.”110

The 1st Division commenced herding all civilians into the Katchin Peninsula on 11

COMPANY B of 1/7 patrols the high ground in the Chimu area on 11 April.

April. The following day, the division began to take into custody all able-bodied men to determine their possible military status. Security and operational efficiency, however, are compatible only up to a certain point, where their interests will inevitably clash. The tactical situation governs which shall take precedence. Consequently, the establishment of control over the civilians in northern Okinawa was held in abeyance until organized resistance was broken and combat troops could be diverted to that task.

From the outset of the drive up the Ishikawa Isthmus an increasing number of Okinawans appeared on the roads. But inasmuch as the primary matter in hand was to find and fix the principal enemy forces as soon as possible, only the few men of military age encountered were detained. The remainder “were allowed to go about their business.”111 When the enemy situation was fully developed, the expeditious destruction of organized resistance was, of course, the paramount consideration. While questionable civilians were detained in the 6th Division area during the period of 12 to 16 April, tactical operations in progress at that time precluded a methodical collection of all able-bodied males, such as that being conducted in central Okinawa. But as soon as the hostile center of resistance on Motobu was reduced, large numbers of Okinawans were brought in to Taira, the center of activities connected with control of the natives within the zone of the 6th Division. There, beginning 16 April, from 500 to 1,500 civilians were interned daily until the end of the northern operation.

General Geiger returned 3/7 to parent control on 15 April. This battalion moved to Chuda on the west coast and commenced active patrolling. The following day, as the 6th Division met with increasing resistance, the 7th Marines reverted to General del Valle’s command and the boundary between divisions was readjusted along the Chuda-Madaira Road. At the same time the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines passed to General Shepherd’s control. Upon moving north, 3/1 was attached to the 22d Marines and ordered to Kawada to assist that regiment in patrolling its extensive zone of responsibility, which covered an area of 140 square miles and included 95 miles of coast line.112

During the final drive of the 29th Marines to clear the Itomi-Toguchi Road on 17 April, an enemy group of 20 men attacked the quartermaster dump of the 22d Marines at Majiya. No stores were damaged and the intruders were driven off, but an hour later the Japanese managed

the partial destruction of a bridge on the coastal road a mile west of Majiya.113 As the enemy’s Motobu defense crumbled, increasing evidence appeared that the Japanese were attempting to evade pursuit by shifting to partisan operations. During the afternoon of 17 April the 4th Marines reported that eight kimono-clad enemy had been seen firing light machine guns. A wounded woman was picked up who claimed she had been in company with 50 Japanese soldiers with plans to go to the Ishikawa Isthmus from Motobu.

Company G of 2/22, moving down from Hedo Misaki, joined with Company K of 3/22, which had crossed the island and was advancing from the south, at Aha on the east coast on 19 April. For the next few days units of the 6th Marine Division reorganized and commenced movement to assigned garrison areas to conduct vigorous patrols to locate any remaining enemy resistance. Additionally, the FMF Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion was attached to the 6th Division, and preparations were set afoot to seize and occupy the small islands lying off the Motobu Peninsula.

Following a night reconnaissance in rubber boats, the battalion, transported by armored amphibians, seized Yagachi Shima on 21 April. A leper colony of some 800 adults and 50 children was located on this island, but no resistance was encountered.

Because aerial reconnaissance had reported Sesoko Shima to be occupied and defended, it was decided to launch an attack on that island with one reinforced regiment. But preliminary to the attack, a native was captured during an amphibious reconnaissance of the objective who revealed that the island was probably not occupied. A successive physical reconnaissance confirmed his statements.114 Consequently, Major Jones’ command was also assigned this mission, and the battalion occupied Sesoko Shima on 22 April. Although no opposition was met, the operation was interfered with by more than 100 civilians, moving by canoe from islands to the west where food was running low, and “considerable difficulty was involved in coralling and controlling” them.115 On 23 April the 6th Reconnaissance Company, also mounted on and supported by LVT(A)s, executed a daylight landing on Kouri Shima, likewise finding no resistance.

Meanwhile, 1/22, patrolling the 6th Division rear area, killed 35 of the enemy in a fire fight near Nakaoshi on 22 April. The next day this battalion contacted a strong enemy force in the mountainous area to the east of Nago. These troops, numbering some 200 men who had escaped from the Motobu Peninsula, were firmly entrenched in previously prepared positions which included caves and pillboxes.

Companies A and B engaged this force and killed 52 of the enemy before a dwindling supply of ammunition made it necessary to break off the action. On 24 April, 1/22 returned to the scene of the previous day’s engagement and with 4/15 in direct support reduced the strong point.116Toward evening a Japanese officer and two NCO’s manning a mortar were killed and at their deaths the remainder fled. Patrol action continued in this trackless region on the 25th, and 1/22 completed the mission of eliminating the enemy pocket.117

On 23 April, a small group of IIIAC military police was extricated from an ambush by a detachment from the 7th Marines, and patrolling of the Ishikawa Isthmus was immediately intensified. The 7th was reinforced with 2/1, and all available war dogs were attached to that regiment. At the same time more stringent regulation of travel was imposed within the IIIAC area, and the movement of single vehicles within the corps zone in hours of darkness was prohibited.118

In the meantime, while the 29th Marines remained on the Motobu Peninsula, the 4th Marines moved to its assigned area in northern Okinawa. At Kawada 3/4 relieved 3/1, which returned to parent control on 23 April. In the succeeding two days the remainder of the regiment was disposed with 2/4 at Ora, and 1/4 with the regimental troops and headquarters in

the vicinity of Genka, a small village five miles up the west coast from the juncture of the north coast of Motobu with the main portion of the island.119 With Colonel Shapley’s assumption of responsibility to seek out and destroy stragglers in what had been the southern half of the 22d Marines’ area, 1/22 prepared to move to Hentona on the west coast midway between Motobu and Hedo Misaki, and just south of Ichi from whence 3/22 had been operating since 16 April.120

All units continued combing the mountainous interior for remnants of the Udo Force and semi-independent guerrilla bands.121 With the exception of an occasional flushing of individuals or small groups, results of patrols were usually negative. But during the afternoon of 27 April a reconnaissance patrol of 3/4 sighted a hostile column of about 200 men moving through the northeast corner of the regimental area toward the east coast.122 These enemy troops were believed to be survivors of the Battle for Motobu, who had infiltrated in groups of 20 to 40 from the peninsula by way of Taira, and would probably attempt to escape to the south. Immediate steps were taken to run the fugitives to earth. Two battalions of the 22d were ordered to proceed southward to intercept the column, while 3/4 moved inland from Kawada.

Soon after its arrival at Hentona in the late afternoon of 27 April, 1/22 commenced a forced night march which continued until 2300, at which time the battalion bivouacked until daylight. At dawn 3/22 (less Company I)123 proceeded

MORTARMEN of the 22d Marines proceed in route column toward the northern tip of Okinawa.

inland on a cross-island trail 1,000 yards to the north of, and parallel to, the advance of 1/22. Inasmuch as the quarry was expected to be in the zone of the 22d Marines when contact was made, 3/4 was attached to the 22d. Two battalions of artillery backed up the three infantry units, with 1/15 in direct support of 1/22 and 3/22, and 4/15 in direct support of 3/4.124

The 3d Battalion, 4th Marines moved out in the early morning of 28 April, and shortly before noon Company K established firm contact. Company L was immediately committed to a flanking action, while Company I was employed for evacuation and trail security. During the three-hour fire fight that ensued Company K killed 81 and Company L 28 of the enemy with a loss of one killed and eight wounded.125

Meanwhile, 1/22 had resumed the advance at 0715 and had encountered small scattered groups of the enemy. But because of the difficult terrain this unit was unable to reach the scene of action and halted to go into bivouac at 1800. The 3d Battalion of the 22d was also still on the march at 1500 when 3/4 radioed that the enemy had been destroyed, whereupon

Colonel Schneider ordered 3/22 to continue on to the east coast. The 3d Battalion, 4th Marines returned to Kawada and reverted to the control of its regiment. The next day 1/22 returned to the vicinity of Momobaru on the west coast, but 3/22 remained on the eastern side of the island and patrolled the area in which 3/4 had fought the action of 28 April.126

The partisan warfare in the IIIAC area did little to delay the reduction of organized resistance in northern Okinawa, and the casualties the enemy inflicted did not impair combat efficiency. But the guerrillas attained their primary objective by forcing attrition in the sense that their activities necessitated the employment of a relatively inordinate number of combat troops on missions secondary to the main effort.

Inasmuch as the essence of guerrilla tactics is the avoidance of a decisive engagement, it follows that a multiple envelopment normally constitutes the quickest and most effective countermeasure of organized units for bringing the irregular to battle. In turn, this maneuver form requires that the counterguerrilla forces possess overwhelming numerical superiority over their adversaries.

The poorly trained and equipped Boeitai whose armament was often limited to grenades or sharp pointed bamboo spears,127 made a substantial contribution to the over-all partisan mission. The native Okinawan, with his thorough knowledge of the terrain, for the most part avoided manning fixed fortifications and conducted a fluid defense in the broken terrain of the Okinawan hills. His offensive efforts consisted of individuals and groups of two or three of the Boeitai making night forays against supply installations; striking at corps switching centrals; cutting telephone wires and ambushing the line repair parties; and attacking water points and hospitals. While these assaults in themselves were essentially abortive, they nevertheless necessitated the provision of adequate security detachments, which were sometimes of platoon or company strength.

After Motobu Peninsula had been cleared on 20 April, Tenth Army tightened the restrictions on the native populace. On this date all combat units were directed to intern all civilians in their areas regardless of age or sex, and prohibit their movement unless accompanied by an armed guard.128 To carry out this directive, eight internment centers were designated by General Geiger for IIIAC units. Shortly thereafter the number of collection points in the Marines’ area was reduced to three: Katchin Peninsula, Chimu, and Taira.

Despite these precautions harassment still continued during the last week of April. In the 7th Marines’ area, a truck sent to pick up a patrol was fired on by an old man and a young boy. The driver was wounded, a lieutenant riding with him was killed, and the pair made off with the Marines’ carbines when they left the scene. The same day the 7th killed a Japanese corporal with a kimono on over his uniform, and a patrol of the 1st Pioneer Battalion killed two of the enemy in a cave with their uniforms lying nearby.129 On the last day of April a jeep was ambushed by what was believed to be a mixed group of soldiers and civilians.130

As the last significant combat by Marines was being fought in northern Okinawa on 28 April, Colonel Walter A. Wachtler, IIIAC operations officer, attended a conference at Tenth Army headquarters concerning the future

employment of the corps in southern Okinawa. The 1st Marine Division had been placed in Tenth Army reserve on 24 April and plans were made to commit it in the south as a much needed reinforcement for the XXIV Corps attack. (See Map 13)

Capture of Ie Shima131

The rapid advance of the 6th Marine Division into northern Okinawa after L-Day, led to a reappraisal of plans as originally projected for Phases I and II. As it became evident that Okinawa north of the Ishikawa Isthmus could be taken by an overland advance, naval requirements were reduced to resupply and gunfire support operations. Ships which might have been needed for an amphibious assault on Motobu Peninsula, a possibility considered in all advance planning, were now available for the capture of Ie Shima. Admiral Turner lost no time in issuing an attack order directing the seizure of the island and its vital airfield. On 10 April, he designated Admiral Reifsnider, who commanded the Northern Attack Force, as Commander, Ie Shima Attack Group (TG 51.21). (See Map 17)

The landing force selected for the operation was the 77th Infantry Division. Its commander, General Bruce, who had remained on board his command ship at Kerama Retto since 26 March, was readily available for planning purposes. His staff and that of Admiral Reifsnider by working closely together were able to complete both the attack and field orders within two days. By 12 April, the 77th Division was committed to its second assault landing in less than a month. The day picked (W-Day) was 16 April and the moment of initial assault (S-Hour) tentatively set for 0800.

The men of the 77th had spent two weeks on board ship monotonously circling in an area about 300 miles southeast of Okinawa where they were relatively safe from air attack. The division’s transron had not escaped unscathed, however. On 2 April, as the ships were sailing for their open sea refuge, they were attacked by a flight of eight Kamikazes. All the Japanese planes were accounted for, but the count included three successful suicide crashes. Two transports and the APD Dickerson were hit.