CHAPTER 9

Reduction of the Shuri Bastion

The 11 May attack of Tenth Army was a massive, coordinated effort to destroy the defenses of Shuri. It inaugurated two weeks of bloody, close-in combat that took the lives of thousands of men. For each attacking division the battle for Shuri took the name and shape of a different terrain feature. Conical Hill dominated the front of the 96th Division. The 77th Division fought for Shuri. The objective of the Marines of the 1st Division was Wana Draw. And for the 6th Division the goal was the capture of Sugar Loaf.

Sugar Loaf Hill1

The three mutually supporting hills of the Sugar Loaf position rose abruptly from surrounding bare terrain. The flanks and rear of Sugar Loaf Hill were blanketed by fire from extensive cave and tunnel positions in Half Moon Hill to the southeast and the Horseshoe to the south. The 6th Division’s analysis of the terrain pointed out that:

. . . the sharp depression included within the Horseshoe afforded mortar positions that were almost inaccessible to any arm short of direct, aimed rifle fire and hand grenades. Any attempt to capture Sugar Loaf by flanking action from east or west is immediately exposed to flat trajectory fire from both of the supporting terrain features. Likewise, an attempt to reduce either the Horseshoe or the Half Moon would be exposed to destructive, well-aimed fire from Sugar Loaf itself. In addition, the three localities are connected by a network of tunnels and galleries, facilitating the covered movement of reserves. As a final factor in the strength of the position it will be seen that all sides of Sugar Loaf Hill are precipitous, and there are no evident avenues of approach into the hill mass. For strategic location and tactical strength it is hard to conceive of a more powerful position than the Sugar Loaf terrain afforded. Added to all the foregoing was the bitter fact that troops assaulting this position presented a clear target to enemy machine guns, mortars, and artillery emplaced on the Shuri heights to their left and left rear.2

The strength of Major Courtney’s embattled group of Marines atop Sugar Loaf on the night of 14-15 May fell away to a mere handful under the ceaseless bombardment and counterattacks of the Japanese. Shortly after midnight Courtney was killed leading a grenade attack against the reverse slope defenders, and the situation of the few remaining men steadily worsened.3 At 0230 Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse ordered his reserve, Company K, to reinforce Sugar Loaf, and the woefully understrength unit moved to the top of the hill and dug in. Counterattacks and infiltration attempts hit all along 2/22’s thin lines during the

night, and at 0630 Company D of 2/29 was attached to the 22d Marines to help mop up the enemy that were fighting throughout the 2d Battalion’s area.

At dawn less than 25 men, many of them badly wounded, remained within 2/22’s perimeter on Sugar Loaf. At 0800 the seven survivors of the Courtney group were ordered off the hill by Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse and shortly thereafter the Japanese again attacked the American outpost. As soon as Company D of 2/29 moved into position on the hill just north of Sugar Loaf, Woodhouse sent a reinforced platoon forward to relieve the remnants (1 officer and 8 men) of Company K. The enemy pressure on Sugar Loaf continued to mount and eventually drove the Marines off the hill. At 1136 the 11 remaining men of the original 60-man platoon drew back to hastily-constructed defenses manned by the rest of Company D.4

The series of enemy counterattacks begun at Sugar Loaf reached at least battalion strength and spread out along a 900-yard front into the zones of 1/22 and 3/29. An intensive preparation fired by NGF, air, and artillery to support the 6th Division attack set for 0800 temporarily stopped the Japanese assault but it soon regained momentum. Until 1315 when the last counterattack effort finally subsided, the troops manning the center of the division line beat off repeated attempts to penetrate their positions. A heavy loss was suffered by 1/22 as a result of the incessant artillery and mortar bombardment that supported the enemy atttack. The battalion commander, Major Thomas J. Myers, was killed, and the commanders of all three rifle companies and the supporting tank company were wounded when the battalion observation post was hit by artillery fire.5 Major Earl J. Cook, the executive officer, took over the battalion and began its reorganization. Companies A and B moved forward on the left of the battalion front during the morning to seize the hill northwest of Sugar Loaf and blunt the force of enemy counterattacks.

The fear of a breakthrough in 2/22’s area caused Colonel Schneider to order Company I of his 3d Battalion to move into blocking positions behind the 2d’s thin lines. At 1220 he notified Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse that his badly depleted battalion would be relieved by 3/22 as soon as possible and that it would then take over the 3d Battalion’s old positions on the right of the division lines.6 By 1615 the relief was completed with Companies I and L occupying 2/22’s old front lines.7 Company D of 2/29 reverted to parent control. The 2d Battalion received a draft of 50 men from regiment to bolster its strength as it moved into new positions along the Asato Gawa.

An abortive counterlanding attempt on the night of 14-15 May had been smashed by naval support craft, but the prospects of further raids prompted division to reinforce its beach defenses. The 6th Reconnaissance Company was attached to 2/22 for night defense, and 2/4, which had been moved across the Asa Kawa at the height of the counterattack threat, went into position west of Asa. Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse was given control of 2/4, which was still in corps reserve, for defense coordination purposes.

During the day the 29th Marines, besides contributing substantially to the repulse of the enemy counterattack, improved its hold on the high ground north of Half Moon Hill. The 1st Battalion, with Company C in assault and A following closely to the right rear, wiped out the pocket of resistance on the regiment’s left flank which had held up the advance on 14 May. By late afternoon Company C had reached the valley north of Half Moon where its supporting tanks came under direct 150mm howitzer fire. Assault troops engaged the enemy reverse slope defenders in a grenade duel and dug in along the ridge north of the valley. Elements of Company A moved up on the right of C to contact 3/29, and Company B linked the 1st Battalion’s lines with the 5th Marines along the division boundary. Freed from enfilade fire

by the reduction of the pocket on its left flank, Company I of 3/29 moved abreast of 1/29 at dusk and tied in with Company G which had borne the brunt of the Japanese counterattack during the day’s action.

The Japanese 15th Independent Mixed Regiment, which faced the 6th Marine Division, suffered heavy casualties on 15 May as a result of its unsuccessful counterattack and the advance of 1/22 and the 29th Marines. The division counted over 585 enemy dead within its zone and estimated that 446 more had been killed by supporting fires or sealed in caves and tombs during mopping-up activities.8 Anticipating General Shepherd’s all-out effort to destroy the Sugar Loaf position, the Thirty-second Army reinforced the 15th IMR on the night of 15-16 May with a “crack” battalion picked from the service and support units of the 1st Specially Established Brigade.9

The seizure of Half Moon Hill was the key to the success of the 6th Division attack plan for 16 May. Once the 29th Marines had cleared the high ground on its left flank, 3/22 was to advance and capture Sugar Loaf. Heavy enemy fire swept the entire front as the assault companies attempted to jump off at 0830. A platoon from Company B of 1/29, accompanied by tanks, passed through the right flank of the battalion line to clear the reverse slope of the ridge occupied by Company C. Devastating small-arms, artillery, AT, and mortar fire hit the tank-infantry teams as soon as they moved out of defilade and drove them back to cover. The fury of opposing fire from the reverse slopes also prevented Company C from moving over the crest of the ridge. The only gain of note in the battalion sector was made by the remainder of Company B which advanced 300 yards down the division boundary to positions abreast of Company C before it too was stopped by vicious frontal and flanking fire.10 At 1400 Lieutenant Colonel Moreau was seriously wounded by an artillery shell which exploded in his observation post, and Major Robert P. Neuffer took command of the battalion.11

The 3d Battalion of the 29th (Lieutenant Colonel Erma A. Wright) spent most of the morning moving into favorable attack positions while the enemy bombarded its front lines with heavy mortars and artillery. At about 1400 tanks moved through the railroad cut northeast of Sugar Loaf and swung into the open valley that constituted the approach to Half Moon. While the tanks fired into the reverse slope of the ridge in front of 1/29 and delivered close-in supporting fire,12Companies G and I made a swift advance across the bare ground and reached the northern slope of Half Moon. Initial resistance was light, but by 1500 the battalion was in serious trouble. Showers of grenades from caves and emplacements on the south slope of the hill hit the men as they attempted to dig in. Machine-gun, rifle, and mortar fire coming from both flanks and the rear crisscrossed the exposed positions. An attempt to give the battalion protection with smoke cover failed to lessen the enemy fire, and slightly before dark Lieutenant Colonel Wright authorized a withdrawal. The assault companies pulled back to their jump-off positions for night defense.13

On the right of the division attack zone 1/22 met intense automatic weapons fire from the outskirts of Takamotoji as it attempted to move into position to support the attack of the 3d Battalion. The Takamotoji area had previously been quiet, and the presence of determined enemy defenders revealed that the Japanese had moved reinforcements into position to block any attempt to flank Sugar Loaf from the direction of Naha. The battalion was unable to occupy the high ground assigned it because of this fire and that coming from the direction of Sugar Loaf and the Horseshoe.

Lieutenant Colonel Donohoo planned to have Company I make 3/22’s main effort as soon as 3/29’s advance covered his flank. The company was to circle and assault Sugar Loaf from the left while Company L advanced its lines to the next high ground to its front and covered the assault with fire on the west and south

SUGAR LOAF HILL, western anchor of the Shuri defenses, seen from a point directly north.

slopes of the hill. Company I moved out with its supporting tanks at 1500 and reached the hill without meeting any serious opposition. Once the assault platoons attempted to drive to the crest, however, they began receiving machine-gun and mortar fire from the enemy defenders. The supporting tank company attempted to flank the hill and fire on the reverse slope but it was stopped by a mine field which claimed one tank.14 Despite the heavy enemy fire the company had fought its way to the top of the hill by 1710 and begun to dig in.

Company L, which had moved out to support the attack shortly after 1500, was pinned down almost immediately by fire from three sides. With 1/22 and Company L unable to get into position to furnish supporting fire on the right and 3/29 forced to withdraw from Half Moon on the left, Company I’s precarious hold on the top of Sugar Loaf was impossible to maintain. Excessive casualties inflicted by enemy gunners on both flanks and the determined defenders of Sugar Loaf itself forced the company back down the hill. Division and corps artillery fired harassing and interdictory fires to prevent the Japanese from attacking Company I as it slowly withdrew to its former positions. During the necessary reorganization of 3/22’s night defenses, enemy artillery shelled the front lines and Lieutenant Colonel Donohoo was wounded. The battalion executive officer, Major George B. Kantner, assumed command.15

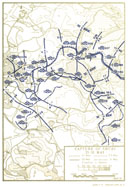

At the close of a day of action that the division called the “bitterest” of the Okinawa campaign, in which its “regiments had attacked with all the effort at their command and had been unsuccessful,”16 the offensive capabilities of the 22d Marines had been reduced to a point where further effort was inadvisable. After assessing his losses in the 16 May attack, Colonel Schneider reported that his regiment’s combat efficiency was down to 40 per cent. Clearly, the 29th Marines would have to carry the burden of the fighting on 17 May. The regimental boundary was shifted to the west to include Sugar Loaf within the 29th Marines’ zone because of the difficulty of coordinating an attack on both Sugar Loaf and Half Moon. (See Map 25)

Map 25

Battle for Sugar Loaf Hill

16-17 May 1945

The 29th Marines attacked with three battalions abreast at 0855 on 17 May. The 2d Battalion on the right, with Company E in assault, was assigned the mission of seizing Sugar Loaf while the 1st and 3d Battalions attacked the Half Moon. In an effort to neutralize the powerful enemy defensive system, an intensive preparation including the fires of 16-inch naval rifles, 8-inch howitzers, and 1,000-pound bombs was laid down on the regiment’s objectives. The assault companies advanced behind a heavy and continual artillery barrage, and each infantry battalion had the support of a company of tanks.

Company A, attacking on the right of 1/29, drove west against the Japanese who occupied the reverse slopes of the battalion’s ridge position. Tank fire, flame, and demolitions finally weakened the enemy fire enough for Company C to cross the crest of the ridge and attack down the hotly-contested southern slope. While Company C mopped up the remaining enemy defenders, Company A renewed its attack and made a swift advance across the valley floor to the forward slopes of Half Moon Hill. Fire from caves and trenches on the hill, from Sugar Loaf, and from the direction of Shuri stopped Company B when it attempted to cross the open ground and extend the battalion’s lines on the left. The positions of the exposed assault platoons of Company A proved untenable without the planned reinforcement, and Major Neuffer authorized a withdrawal to a defiladed area approximately 150 yards forward of the morning’s jump-off line.17

Freed from some of the heavy enfilade fire that raked its front by the advance of Company A on its left, 3/29, with Company H in the lead, fought its way across the valley floor to Half Moon. By midafternoon the battalion was digging in on the forward slopes of the hill but there was no contact between its positions and those of 1/29. At 1635 Colonel Whaling ordered two platoons of Company F to move up and close the gap. The hastily established defensive positions on Half Moon were subjected to terrific bombardment, and the failure of repeated attacks by 2/29 to secure Sugar Loaf exposed the right flank of 3/29 to heavy and accurate fire from the enemy strong point.18 In order to set up a secure night defense that would meet the threat of Japanese counterattacks, 3/29 pulled back when Company A was forced to withdraw on its left. The battalion took up strong positions only 150 yards short of Half Moon and tied in by fire with 1/29 and 2/29 on its flanks.

The first attempt by Company E of 2/29 to reach Sugar Loaf, a wide turning movement using the railroad cut for cover, was checked by enemy artillery fire as soon as the Marines debouched into open ground. A second assault, a close flanking attack around the left of the hill, was stopped by the precipitous nature of its southeastern face. The company reoriented its lead platoons to move up the northeast slope, and at 1700 the climbing assault started. Three times the troops, attacking through extremely heavy mortar fire coming from covered positions in the Horseshoe, reached the crest. Each time a frenzied counterattack drove them off.

At 1830 the fatigued and seriously depleted company made its final assault, once more gaining the fire-swept hill top. A determined counterattack was beaten back, but the company’s ammunition supply was completely exhausted and casualties were so heavy that no men could be spared to evacuate wounded. At 1840 the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel William G. Robb ordered the company to withdraw from Sugar Loaf for the night. During one day’s action 160 men had been killed or wounded in Company E, and Sugar Loaf was still in Japanese hands. At dusk some small measure of repayment for the day’s terrible losses was gained when the enemy was caught attempting to reinforce Sugar Loaf by moving troops across the open ground at its base. Artillery observers concentrated the fire of 12 battalions on the hapless Japanese and completely smashed the attempt.

On 18 May tanks provided the key to a successful assault of Sugar Loaf. Despite mine fields and accurate AT fire which claimed six tanks, a company of mediums reached positions on each flank of the hill from which they could cover the reverse slopes. Company D of

HALF MOON HILL and the corridor leading to the Kokuba Gawa as seen from Sugar Loaf.

2/29 advanced with the tanks and made a double envelopment of the objective. At 0946 the assault platoons reached the top of Sugar Loaf and held their ground despite a fierce grenade and mortar duel with the enemy defenders. The attackers soon moved over the crest to mop up and destroy the caves and emplacements on the south slopes. Deadly mortar fire from covered positions in the Horseshoe blanketed Sugar Loaf, and Company D dug in at about 1300 to hold its gains.

Lieutenant Colonel Robb committed Company F on the right of the battalion zone to reduce the Horseshoe defenses. Supported by fire from the troops on Sugar Loaf and 1/22 on its right, Company F reached the ridge that marked the lip of the Horseshoe depression before it was halted by an intense mortar and grenade barrage. The company withdrew slightly to the forward slopes of the ridge and dug in a strong defensive position for the night.

Impassable terrain prevented the tanks with

Map 26

Battle for Sugar Loaf Hill

18-19 May 1945

1/29 and 3/29 from enveloping Half Moon Hill.19 Their fire support was invaluable, however, to the assault troops of the two battalions who had spent most of 17 May improving and consolidating their positions along the base of Half Moon. The continued strong resistance of enemy defenders in the Horseshoe and on Half Moon after the fall of Sugar Loaf Hill pointed up the importance of the Sugar Loaf position to the Thirty-second Army’s defensive scheme.

During the 6th Division’s advance to the Asato Gawa, the Japanese had countered the threat of a breakthrough at Naha by moving four battalions of naval troops to the area south of the 44th IMB’s front lines. The motley naval units had a thin backbone of men trained for land combat, but most of their strength was derived from inexperienced service troops, civilian workers, and Okinawans attached to Admiral Ota’s Naval Base Force. The lack of training was in part compensated for by a generous allotment of automatic weapons taken from supply depots on Oroku and the wrecked planes that littered the peninsula’s airfield.20 The naval force was to back up the Sugar Loaf position, hold the hills northwest of the Kokuba Gawa, and guard Shuri’s flank should the 44th IMB’s defenses collapse. The Japanese considered that the fate of the left flank of the Shuri position hinged directly on their success in holding the defense area which stretched from the Naha estuary near Kobakura to the outskirts of Shuri.21

By nightfall on 18 May the combat efficiency of the 29th Marines had been seriously impaired by its fight for the Sugar Loaf position. The 6th Division had suffered 2,662 battle and 1,289 non-battle casualties since the start of the Tenth Army attack, almost all of them in the ranks of the 22d and the 29th Marines. A fresh unit was needed to continue the attack with undiminished fervor and General Geiger released the 4th Marines to General Shepherd at 1830. The 29th Marines was to become division reserve subject to IIIAC’s control. The attack plan for 19 May called for the 2d and 3d Battalions of the 4th Marines to relieve the 29th and consolidate the gains of the previous day’s fighting. (See Map 26)

At 0300 the Japanese counterattacked the open right flank of Company F of 2/29 on the edge of the Horseshoe depression. The enemy assault, supported by a heavy bombardment of white phosphorus shells, was strong enough to force the leading elements of the company to withdraw to the southern slope of Sugar Loaf.22 At daybreak Companies K and L of 3/4 began relieving the units of 2/29 on Sugar Loaf, while Companies F and E of 2/4 took over the rest of the 29th Marines’ front. The reliefs were effected smoothly despite the difficult terrain, steady bombardment, and opposition from small enemy groups which had infiltrated the lines during the night. Some advances were made along the regimental front as assault companies seized the most favorable positions from which to attack on 20 May.

The area that had spawned the counterattack on Company F was partially neutralized during the day’s action. The 22d Marines under its new commander, Colonel Harold C. Roberts,23 advanced its left 100-150 yards to the high ground on the flank of the Horseshoe. Companies A and B of 1/22 dug in under enemy artillery and mortar fire to hold the new positions which materially aided in strengthening the division’s line.

Company E of 2/4, which had taken over 3/29’s advanced positions on Half Moon Hill,

sustained a strong counterattack in the late afternoon which began shortly after the relief was completed. By 1700, after a two-hour fire fight, the company had turned back the attackers. However, since its exposed position was still vulnerable to attack from three sides, Lieutenant Colonel Hayden ordered the company to draw back its left flank elements approximately 150 yards to a point where they could tie in physically with Company F.24 For night defense the 4th Marines established firm contact across its front linking up with positions of the 22d on the right and the 5th on the left.

Promising gains were made by both assault battalions of the 4th Marines on 20 May. Jumping off at 0800 behind heavy artillery barrages and tanks, the attacking troops moved rapidly ahead for 200 yards before encountering fierce opposition from the Horseshoe and Half Moon. The 22d Marines on the right furnished fire support to 3/4 in its attack on the high ground which formed the western end of the Horseshoe.

Infantrymen with demolitions and flame throwers followed closely behind the tanks which blasted the cave positions honeycombing the forward slopes of the Horseshoe. By 1600 when the regiment called a halt to the attack to prepare strong night defenses, Companies K and L held dominating ground that overlooked the Japanese mortar emplacements in the Horseshoe depression. Shortly after noon Lieutenant Colonel Bruno A. Hochmuth had committed elements of the 3d Battalion’s reserve, Company I, which had mopped up Sugar Loaf Hill during the morning, to maintain contact with 2/4 on the left and strengthen the front line. Colonel Shapley, anticipating a counterattack in 3/4’s area, alerted 1/4 to back up the Horseshoe defenses. Company B was designated for the job and briefed on 3/4’s situation, routes of approach, possible support, and methods of support.25

The attack of 2/4 on Half Moon developed into a replica of the Sugar Loaf Hill battle during 20 May. Heavy and accurate flat trajectory fire coming from the direction of Shuri heights raked the battalion’s flank, and mortars firing from defiladed positions on the reverse slopes of

TANKS evacuate wounded as men of the 29th Marines continue the attack on the Sugar Loaf position.

Half Moon covered the entire zone of advance. Resistance increased sharply throughout the morning as the enemy strove desperately to hold the commanding ground.

At about 1000 Company E, which had been replaced by Company G for the attack, was committed again on the left of the battalion line to maintain contact with the 5th Marines. With all three of his rifle companies in assault and the casualty toll mounting, Lieutenant Colonel Hayden decided to reorient his attack objectives from the front to the flanks of Half Moon. While Company F held its lines in the center and supported the advance by fire, Company E was to attack south down the division boundary and Company G was to drive past Sugar Loaf and then turn to attack the reverse slopes of Half Moon from the southwest. One company of tanks would furnish overhead fire support while a second company split to attempt a double envelopment with Companies G and E.

By 1245 the details of coordination were completed and the attack was renewed. The tanks with Company G negotiated the mine field that guarded the right flank of Half Moon and provided neutralization fire that enabled the infantry to seize and hold the western end of the hill. The tanks with Company E were unable to reach positions where they could fire on the

reverse slopes of Half Moon because of the operational failure of a tank bulldozer which attempted to make an approach route to the east of the hill.26 Consequently, Company E was subjected to heavy grenade and mortar barrages as it advanced, and it eventually had to dig in on Half Moon’s forward slopes.27 The night positions of 2/4 and the Japanese were close but separated by a killing zone along the hill crest swept by continual enemy and friendly mortar and artillery fire.

The anticipated counterattack against the 4th Marines materialized at about 2200 when a Japanese group of battalion-size struck the positions of Companies K and L of 3/4. Prepared concentrations by six artillery battalions were fired as soon as the attackers revealed themselves, and constant illumination was maintained over the area by naval support ships.28 In a two-hour-long wild melee fought by the weird light of flare shells, the battalion beat back the attack. Lieutenant Colonel Hochmuth committed Company B, which moved “with perfect timing”29 to join the close-quarter combat and help blunt the attack spearheads. By midnight the few Japanese who had penetrated the lines were either dead or attempting to withdraw. Investigation in the morning light revealed 494 enemy dead and indicated that the attack had been made by fresh units, including some naval troops.30 The frenzied counterattack showed how determined the enemy was to safeguard Shuri’s western flank.

The division attacked on 21 May with its objective the upper reaches of the Asato Gawa. The 4th Marines made the main effort with the 22d conforming to its advance and delivering supporting fire. Under its new commander, Lieutenant Colonel George B. Bell,31 the 1st Battalion, less Company C in regimental reserve, attacked in the center of the line down the south slopes of Sugar Loaf toward the eastern extremity of the Horseshoe. Progress was slow and the fighting bitter as Companies A and B struggled to reach the river. A steady, soaking rain fell throughout the morning and most of the afternoon, making the loose, shell-torn ground muddy and treacherous. Adequate supply and evacuation through the thick, clinging cover of mud were almost impossible. The day’s advance of approximately 200 yards was won only by dint of prodigious efforts by men who had to fight the weather as well as the numerous enemy pockets that held out all along the river approaches.32

The 3d Battalion drove down into the extensively tunneled interior of the Horseshoe, using demolitions and flame throwers to wipe out resistance in the nest of enemy mortar positions. Companies K and I halted their advance in midafternoon and set up a solid defense line approximately halfway between the Horseshoe and the river.

Advances in 2/4’s zone of action were negligible because of the rugged terrain which prevented effective tank support and the intense mortar and artillery fire brought to bear on all ground exposed to the Shuri heights. After the fifth day of limited advances in the Half Moon area General Shepherd was convinced that the enemy power that prevented the capture of Half Moon was centered in the Shuri area, outside of the division zone of action. As a consequence, after a thorough estimate of the situation was prepared, he determined to establish a strong reverse slope defense on his left, “making no further attempt to drive to the

southeast in the face of Shuri fire, and to concentrate the division’s effort on a penetration to the south and southwest.”33 He felt that such a maneuver would partially relieve the division of the menace to its left flank, and at the same time give added power to the drive to envelop Shuri from the west.

At midnight on 21 May heavy rains again began to fall, seriously impeding efforts to resupply assault troops and replenish forward dumps. The major obstacle to the success of the 6th Division’s new plan of attack was not the fiercely resisting enemy defenders, but the unrelenting torrents of water that poured out of the heavens and rapidly turned southern Okinawa into a sea of mud.

Wana Draw34

On 14 May a mop-up patrol from the 1st Engineer Battalion discovered a leaflet on the body of an enemy infiltrator in the 1st Division’s rear area. Purportedly written by a wounded prisoner from the 96th Division it warned in atypical English that:

. . . the battles here will be 90 times as severe as that of Yusima Island [Iwo Jima]. I am sure that all of you that have landed will lose your lives which will be realized if you come here. The affairs of Okinawa is quite different from the islands that were taken by the Americans.35

If the crude Japanese propaganda was intended to halt the Marine attack, it was patently unsuccessful. The promise of bitter resistance, however, was amply fulfilled by the defenders of Wana Draw.

In constructing the Wana position the Japanese had “taken advantage of every feature of a terrain so difficult it could not have been better designed if the enemy himself had the power to do so.”36 With this natural advantage, the enemy had so organized the area that in order to crack the main line of resistance it was necessary for the 1st Marine Division to wheel towards Shuri and attack directly into the heart of the city’s powerful defenses. Any attempt to drive past Shuri and continue the attack to the south would mean unacceptable losses inflicted by artillery, mortar, automatic-weapons, and rifle fire coming from the heights that commanded the division’s flank and rear areas. (See Map 27)

The southernmost branch of the Asa Kawa wandered across the gently rising floor of Wana Draw and through the northern part of Shuri. The low rolling ground bordering the insignificant stream was completely exposed to enemy fire from positions along the reverse slope of Wana Ridge and the military crest of the ridge to the south. At its mouth Wana Draw was approximately 400 yards wide, but it narrowed drastically as it approached the city and the ridge walls closed on the stream bed. Guarding the western end of the draw was Hill 55,37 rugged terminus of the southern ridge line. The hill bristled with enemy guns whose fields of fire included the whole of the open ground leading to the draw. Defending the Wana position was the 64th Brigade of the 62d Division with remnants of the 15th, 23d, and 273d Independent Infantry Battalions, the 14th Independent Machine Gun Battalion, and the 81st Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion under its command.38

At 0630 on 15 May the 5th Marines completed the relief of the 1st, and Colonel Griebel assumed command of the zone of action west of Wana. The 2d Battalion was in assault with the 3d in close support and the 1st in reserve. On the recommendation of the regimental and battalion commanders of both the 1st and 5th Marines, the division decided to subject the high ground on both sides of Wana Draw to a thorough processing by tanks and self-propelled 105mm howitzers before 2/5 attempted to advance across the open ground at the mouth of the draw.39

With Company F of 2/5 providing fire teams for protection against suicide attackers, nine tanks from Company B, 1st Tank Battalion

spent the morning working on the positions at the mouth of the draw. The tanks drew heavy small-arms, mortar, artillery, and AT fire, and accompanying infantry was dispersed to reduce casualties. Because of the open area of operation, the fire teams were still able to cover the tanks at relatively long-ranges. Both sides of the draw were honeycombed with caves and the tanks received intense and accurate fire from every sector at their front. During the morning one 47mm AT gun scored five hits on the attacking armor before NGF silenced it.

About noon the tanks withdrew to allow an air strike to be placed in the draw and then return to the attack in reinforced strength. Naval gunfire again silenced a 47mm gun that took the tanks under fire, this time before any damage was done.40 With the approach of darkness the tanks pulled out of the draw pursued by a fury of enemy fire. The 5th Marines, convinced “that the position would have to be thoroughly pounded before it could be taken,”41 scheduled another day of tank-infantry processing for Wana Draw before making its assault.

The 7th Marines spent 15 May reorganizing its companies, improving its positions, and mopping up the area around Dakeshi. Forward observers, liaison parties, and spotting teams concentrated on reducing known enemy strong points on Wana Ridge with extensive artillery, air, and NGF bombardment. At 2100 the 1st Battalion received orders from regiment to execute a fake attack on 16 May, with troops to concentrate for the jump-off while all supporting weapons fired a preparation.42

At daylight the troops moved into position, and at 0755 the preparatory barrage for the feint began. The area to the front was smoked by 81mm and 4.2-inch mortars. After 15 minutes the barrage was lifted to induce the Japanese to leave their covered cave positions and man open emplacements and entrenchments to repulse the expected attack. At 0825 supporting weapons opened fire again with undetermined results.

At 0950 the 7th Marines notified Lieutenant Colonel Gormley that an air strike on Wana Ridge was scheduled for 1000 and that he was to send patrols forward immediately following the strike to feel out enemy resistance. When the planes were delayed, Gormley requested cancellation of the mission and dispatched patrols from Company C to the ridge under cover of a mortar barrage. The patrols advanced without meeting any resistance until they approached the western end of Wana Ridge, where they came under vicious grenade and machine-gun fire. Counterfire was immediately laid down by the battalion’s 81mm mortars and the patrols were able to occupy the western end of the ridge.

Orders were issued to the outpost to hold its ground, and reinforcements from Company C were dispatched to the ridge. At 1240 one platoon of Company A was sent forward to assist Company C, and at 1536 the rest of Company A was committed. Assault teams attempting to expand 1/7’s hold on the ridge were met by showers of grenades from enemy troops hidden among the burial vaults and jagged coral outcroppings. A counterattack attempt was broken up by supporting weapons, but stiff resistance continued. With darkness the battalion’s forward elements were forced to withdraw to secure night defense positions on the plateau just north of the ridge where contact was established with 2/5 to right rear and 3/7 to the left rear. During the day the 3d Battalion had occupied 1/7’s former positions on Dakeshi Ridge.43

Tanks assigned to the 7th Marines had furnished direct overhead fire support to 1/7 from positions on Dakeshi Ridge, while the tanks with 2/5 had spent another busy day burning and blasting positions in Wana Draw. Working in relays, the tanks, supported by fire teams of Company F, ranged as far into the draw as Wana where three mediums and a flame tank completed the job of destruction of the village started by artillery, air, and NGF. Antitank fire disabled two tanks during the morning’s action, but observers spotted the gun flashes of two 47mm’s, and the main battery of the Colorado was brought to bear on the positions, destroying both guns.44 Another tank was lost to

OBJECTIVES of the 1st Division’s advance during day.

a mine and had to be abandoned and written off. Although strenuous attempts were made to retrieve tanks that were temporarily disabled, enemy fire usually blocked rescue attempts. If the tanks were left in the field overnight they were invariably destroyed by Japanese demolition parties and quite often used as pillboxes by the enemy defenders. At nightfall when the tanks retired, they had expended almost 5,000 rounds of 75mm and 175,000 rounds of .30 caliber ammunition plus 600 gallons of napalm on targets on the ridge and in the draw.45 After two days of intensive preparatory fire the 5th Marines was ready to attempt the attack on Wana Draw.

Throughout the morning of 17 May tank-infantry teams of 2/5 again worked on enemy positions in the mouth of the draw. Company F kept contact with the 7th Marines in its attack on Wana Ridge, but was unable to hold advanced positions near the western tip of the ridge when a heavy enemy mortar and artillery barrage forced the advanced elements of the 7th to withdraw. On the right of 2/5’s zone of action, Company E was more successful in penetrating the Wana Draw defenses.

The company’s objective was Hill 55 at the mouth of the draw. Using the railroad embankment along the division boundary for cover and advancing across the open ground behind tanks, the company reached the base of the hill before it was pinned down by heavy small-arms and mortar fire coming from the left and left front. Two supporting tanks were disabled by mines,46 and it was decided to withdraw the company under cover of fire from the two remaining tanks. A reorganization was effected behind the protection of the railroad

embankment, and at 1700 a platoon of Company E with six tanks attacked toward the hill again. This time a strong point was established on the western nose of the hill and held. Supplies and ammunition were brought up to the platoon outpost by tanks since the low ground leading to the hill was swept by machine-gun and rifle fire coming from Wana Draw.47

The 3d Battalion, 7th Marines relieved 1/7 at daybreak on 17 May and attacked with two companies toward Wana Ridge. Company I on the right seized and held the plateau that led to the western nose of the ridge line, while Company K, with the support of 12 gun and two flame tanks, attempted to secure the ridge crest northeast of Wana village. As soon as the company reached the ridge the enemy concentrated his fire against the assault platoons. Smoke grenades were used in an attempt to blind the tanks and limit the effectiveness of their supporting fire.48As the day wore on the position of Company K, beset from the front and both flanks, became untenable, and at 1700 the Marines pulled back to Dakeshi to set up night defense.49 Late in the afternoon Lieutenant Colonel Hurst sent his reserve, Company L, up to reinforce Company I, prepared to assist the attack on the ridge the following morning.50

After a night of sporadic bombardment from enemy artillery and mortars, 3/7 again attempted to gain a foothold on Wana Ridge. During the morning supporting weapons concentrated their fire on the forward slopes and crest of the objective and at noon Company I, followed by a platoon of Company L, jumped off and fought its way to the ridge. The assault troops’ gains “were measured in yards won, lost, and then won again.”51 Finally, mounting casualties inflicted by enemy grenade and mortar fire forced Lieutenant Colonel Hurst to pull back his forward elements and consolidate his lines on positions held the previous night.52

On the right flank of the division front the isolated platoon from Company E of 2/5 was unsuccessful in exploiting its hold on the western slopes of Hill 55. The men were driven to cover by intense enemy fire, and tanks again had to be called upon to supply ammunition and rations to the outpost.

During the morning operations the 5th Marines laid protective fire with tanks and assault guns along Wana Ridge to support 3/7’s advance. At noon, under cover of this fire, Company F sent one rifle platoon and an attached platoon of engineers into Wana village to use flame throwers and demolitions against the enemy firing positions in the ruins. Numbers of grenade dischargers, machine guns, and rifles were found in Wana and the tombs behind it and destroyed. Further advance into the draw was not feasible until the 7th Marines could occupy the high ground on the eastern end of the ridge and furnish direct supporting fire to troops advancing in the draw below. At 1700 the troops were ordered to return to their lines for the night.53

In many ways the action of 19 May was a repetition of that on the previous four days. The 7th Marines again made the division’s main effort, and the 5th Marines operated against the Japanese positions at the mouth of Wana Draw. All morning the ridge underwent a thunderous preparation from artillery, tanks, mortars, and weapons company howitzers in an effort to neutralize enemy fire. However, when Company I of 3/7 jumped off shortly after 1200 it ran into immediate enemy opposition. The company succeeded in reaching the western nose of Wana Ridge by 1555 by dint of fighting its way through a heavy mortar barrage. The weary troops then withdrew a short distance under enemy fire in order to be relieved by elements of 3/1.54The 1st and 2d Battalions of the 7th Marines had been relieved by their opposite numbers of the 1st Marines in their positions near Dakeshi earlier in the day. With the relief of 3/7 by 3/1 Colonel Mason assumed responsibility from Colonel Snedeker for the

WANA RIDGE, rugged barrier in the path of the 1st Division, is shown looking southeast toward Shuri.

capture of Wana Ridge, and the 7th Marines became division reserve.

Despite the fact that tanks with the 5th Marines had worked on the defenses at the mouth of Wana Draw for almost a week, new positions were noted daily and old positions, exposed by tank fire, were rebuilt and recamouflaged each night.55 The defenses that blocked the mouth of the draw were duplicated and multiplied as the ridges on either side narrowed and grew steadily higher and more rugged. The eastern terminus of Wana Ridge, 110 Meter Hill56 on the northwestern outskirts of Shuri, overlooked the zones of action of both the 1st and 77th Divisions, and its defending fire was a potent barrier to the capture of Shuri and the reduction of Wana Draw. On 20 May 110 Meter Hill was made the objective of a coordinated attack by the 1st Marines and the 305th Infantry with 2/1 moving into the 77th Infantry Division’s sector to gain the most favorable route of approach.

Sparked by the presence of the rested and rebuilt57 1st Marines, the 1st Division made substantial progress on 20 May. Using the road running east from Dakeshi as a line of departure, Company G of 2/1 jumped off at 0815 supported

by tanks, self-propelled guns, 37mm’s, and overhead machine-gun fire. The assault troops surged ahead rapidly covering 600 yards to the base of the battalion objective, 110 Meter Hill. Enemy reaction was violent, and Company G suffered heavy casualties, including the company commander, from mortar and machine-gun fire. At about 1230 Lieutenant Colonel Magee ordered Company F to be prepared to pass through Company G and continue the assault.

At 1525 Company F attacked toward the high ground, passing through Company G which delivered suppressive fire on the ruins of Wana. Company F was unable to occupy the crest of the objective in the face of bitter resistance from reverse slope defenders. The assault troops dug in on the hill, and Lieutenant Colonel Magee sent Company E forward to extend the battalion’s line on the left. A considerable gap that existed between the Marine and Army forward positions was thoroughly covered by interlocking bands of machine-gun fire and mortar concentrations.58

The 3d Battalion of the 1st Marines tied in with 2/1’s lines for night defense after seizing a firm hold on the rest of the northern slope of Wana Ridge during the day’s attack. Companies I and K moved out at 0845 and shortly thereafter closed to grenade range with the defenders of the ridge. The assault platoons, closely supported by tanks and armored flame throwers, spread out along the ridge, burning and blasting the innumerable caves, pillboxes, and weapons emplacements that defended the forward slopes. At 1140 two platoons of Company L, in compliance with Colonel Mason’s orders, started carrying 55-gallon drums of Napalm up to the positions of Company I with the intention of splitting them open, rolling them down the steep slopes of the ridge into the Japanese positions at the head of Wana Draw, and setting the flame mixture afire with white phosphorous grenades.

The working parties were only able to manhandle three of the heavy and awkward drums up to Company I’s positions by 1500. When these were split open at 1630, rolled into the draw, and set afire, their forward progress was stopped about 50 yards down the reverse slope by an enemy entrenchment. The flame seared a small part of the Japanese defenses, but its effect was not potent enough to give Company I an entering wedge into the reverse slope positions. While it was still light, the 3d Battalion set up night defenses along the ridge crest with Company K tied in with 2/5 and Company I with 2/1. Because the troops could not dig in very deep in the hard coral that formed the ridge, casualties from enemy mortar and artillery shelling were high. The night positions of the defenders of Wana Draw and the Marines were separated by a few scant yards of shell-blasted ground.59

The objective of the 5th Marines’ attack on 20 May was the low ridge running roughly southwest from Hill 55 along the Naha-Shuri Road. While Company G maintained contact with the 4th Marines at Half Moon Hill along the division boundary, Company E made the main assault. The time of attack, originally scheduled for 0730, was delayed an hour to increase the effect of the tank, assault gun, and artillery preparation. The assault progressed exceedingly well behind a continuous artillery barrage, and at 0930 Company E was involved in close fighting against Japanese in positions along the ground that bordered the road. Engineer mine-removal teams cleared a path for tanks to circle the battle from the direction of Wana Draw and take the defenders from the rear. By noon tank-infantry action had enabled Company E to secure its objective.

The next high ground to the south, Shuri Ridge, was the western extension of the height on which Shuri Castle was situated. Heavy small-arms and mortar fire from this ridge raked Company E’s position throughout the afternoon, but continual artillery fire, point-blank tank fire, and two heavy rocket barrages finally silenced the enemy guns. Night activity, except for the usual sporadic mortar and artillery fire, was negligible, and shortly before dawn the troops were relieved on the front line by Company C of 1/5.60

The mission of 1/5 on 21 May was to maintain sufficient troops in the vicinity of Wana Draw

at Hill 55 to assist the attack of the 1st Marines and to patrol aggressively forward toward Shuri Ridge and the high ground to the east of Half Moon Hill. Tank-infantry patrols from Companies B and C scouted the ground to the south against intense machine-gun and mortar fire. Tank commanders, using their vehicles as armored observation posts, successfully called down artillery fire on point targets at close ranges.61 Front line positions on Hill 55 and along the division boundary were advanced slightly to put the troops into more favorable positions for an all-out attack.

On 21 May Lieutenant Colonel Ross assumed command of 3/1 to replace Lieutenant Colonel Sabol who was transferred to the 7th Marines as regimental operations officer.62 Ross’ attack plan called for fire teams of Company L to work with relays of tanks in Wana Draw during the morning in an attempt to clean out the reverse slope positions on Wana Ridge. Companies K and I would support Company L’s advance from the ridge crest and be prepared to attack across the draw on order with Hill 55 and the ridge line to the east as their objective.

During the early part of the afternoon the tank-infantry teams of Company L continued to work on positions in the draw against increasingly stiffer enemy opposition. At about 1500 Company K started across the mouth of the draw, and Ross asked Colonel Mason for a company from 1/1 to set up a secondary line on Wana Ridge to back up 3/1’s attack. Company I, attempting to follow Company K’s assault, was pinned down in the draw by heavy machine-gun and mortar fire. By 1800 Company K had fought its way up Hill 55 and tied in with 1/5, but it was unable to advance any farther to the east toward Shuri. Since Companies I and L were unable to reach the southern ridge line and advance up Wana Draw in the face of withering enemy fire, Ross ordered them to withdraw to Wana Ridge for the night defense.63

In response to Lieutenant Colonel Ross’ request, Colonel Mason attached Company C of 1/1 to the 3d Battalion. For night defense Company C occupied Company I’s 20 May position tied in with Company L on the right and Company F of 2/1 on the left.

The 2d Battalion made repeated attacks on 110 Meter Hill and the rest of Wana Ridge in its zone on 21 May. The terrain was so steep and irregular that tanks were limited to overhead supporting fire. The deep cleft at the head of Wana Draw prevented the armor from reaching the reverse slopes of 110 Meter Hill, and the enemy defenders continued to hold out. On the left of the battalion, Company G mopped up enemy opposition in the northern outskirts of Shuri, but it was unable to exploit its success by turning the flank of the commanding hill. Resisting the advance of Company G were elements of the 22d Independent Infantry Battalion, the Thirty-second Army’slast remaining first-line infantry reserve, which had been thrown into the battle to hold the area round 110 Meter Hill.64

Lieutenant Colonel Magee concentrated the fire of all his battalion’s supporting weapons on positions in Wana Draw, but Companies E and F were unable to move down the reverse slopes of Wana Ridge in the face of bitter opposing fire from extremely close range. The accuracy of enemy mortar and artillery fire made it clear that the battalion was holding a preregistered impact area, since lowering skies and occasional rain squalls obscured the view of both enemy and friendly observers. Despite a steady drain of casualties the battalion maintained its forward positions. Company G linked 2/1’s lines by fire with the 77th Division on the left, and Company F tied in for night defense with Company C of 1/1.

At midnight the day’s intermittent rain increased to a steady downpour, and at 0200 the Japanese, capitalizing on the poor visibility, swarmed up Wana Ridge to attack Company C.

For four hours a grim hand grenade battle seesawed back and forth across the crest of the ridge before the Marines were able to restore their lines at daylight.65 The enemy lost 180 men in their unsuccessful attempt to break the line held by Company C.66

So much of the success of the 1st Division’s attack depended upon the tank-infantry team that the beginning of heavy rains was a major disaster. The ferocity of enemy resistance at Wana Ridge, where tank support was severely limited by terrain barriers, seemed undiminished. With the only tank country, that in the zone of the 5th Marines, rapidly turning into a veritable swamp, the 1st Division faced the prospect of a bloody stalemate with the odds distinctly in favor of the Japanese. (See Map 23)

Shuri Heights and Conical Hill67

For the XXIV Corps the period from 15-21 May was marked by a series of costly battles for the possession of hill strong points that guarded the approaches to Shuri and Yonabaru. Determined and agonizingly slow advances brought brief and bloody fame to rugged hills and ridges called Chocolate Drop, Flat Top, Ishimmi, Hog Back, Dick, Love, Oboe, and Sugar. And finally, when success was in sight and Shuri’s flank was turned, driving rain and seas of mud bogged the attack to a virtual standstill.

The 77th Infantry Division was faced, as was the 1st Marine Division, with the unenviable task of maintaining steady, grinding pressure on the defenses of the core of enemy resistance at Shuri. On 15 May the 305th Infantry continued its dogged advance through the irregular terrain west of the main Ginowan-Shuri highway and east of Dakeshi. No prominent terrain features stood out in the regiment’s zone of advance to keynote its action. Its objective was the northern outskirts of Shuri, and its path on this day and succeeding days was blocked by countless small hills, ridges, and ravines fiercely defended by elements of the Japanese 64th Brigade and 32d Regiment.

On the left of the 77th Division sector several prominent hills and ridges completely dominated the rolling ground east and northeast of Shuri. The 306th Infantry had exhausted its strength in ten days of constant battling to reach these objectives and it was relieved on the morning of 15 May by the 307th Infantry. From right to left across the front of the fresh assault regiment the key ground was Ishimmi Ridge, 500 yards long and 110 meters high, which overlooked the Ginowan-Shuri highway; Chocolate Drop Hill, a rounded peak 130 meters high that rose abruptly from the rough plateau between the highway and the division boundary; and 140-meter Flat Top Hill, a companion peak to Dick Hill in the 96th Division zone, which effectively blocked the road from Kochi to Shuri that generally paralleled the division boundary.

On 15 May 3/307 fought its way up the forward slopes of Chocolate Drop and reached the base of Flat Top Hill against determined resistance. On the right of the regiment’s zone the 2d Battalion, driving toward Ishimmi Ridge through the open highway valley, managed to gain a tenuous hold on a low finger ridge that extended southwest from Chocolate Drop. For night defense the regiment withdrew its assault troops from their forward slope positions to guard against the inevitable grenade duels and infiltration attempts.

The 382d Infantry of the 96th Division supported the attack of 3/307 on Flat Top Hill on 15 May in conjunction with its own assault against Dick Hill, which extended south from Flat Top along the division boundary. Behind a covering barrage of artillery fire placed on known enemy gun positions and observation points, 3/382 worked its companies up the steep slopes of the hill by infiltration. By 1700 three companies of the 3d Battalion and one of the 1st had reached the hill crest, but all attempts to cross the skyline were driven back by raking machine-gun fire. Night positions were taken up just short of the crest, only 50 yards from the Japanese defenders.

The 383d Infantry, with 2/381 attached, made

little forward progress during the day against the extremely heavy enemy fire coming from the hill complex southwest of Conical’s peak. Supporting weapons were used effectively to knock out enemy emplacements in the vicinity of the front lines and to cover strong probing patrols that felt out the reverse slope defenses of Conical Hill. The defenses were formidable, well-organized, and manned by the enemy’s 89th Regiment which was determined to hold the vital eastern flank of the Shuri bastion.68 (See Map 28)

The following day 2/383, attempting to capitalize on the information its patrols had gained on 15 May, attacked down the southeast slopes of Conical Hill. The battalion made only slight gains but one of the supporting tank platoons on its left flank broke through the cordon of enemy fire that swept the coastal flats and advanced 1,000 yards to the northern outskirts of Yonabaru. The tanks immediately started bombarding the town, but the intense enemy fire prevented the infantry from exploiting the armor’s success and the tanks withdrew after exhausting their ammunition supply.

The 1st Battalion of the 383d again attempted to penetrate the hill fastness southwest of Conical and again was pinned down almost immediately. One platoon that did slip through the enemy fire barrier was practically annihilated on the forward slopes of the battalion’s objective, Love Hill, by the crossfire of an estimated 50 machine guns that opened up from front, rear, and both flanks.

The hold that the 382d Infantry had seized on Dick Hill was exploited on 16 May. Early in the morning 2/382 passed through the lines of 1/382 and attacked across the crest of the hill. By 1400 the battalion had successfully wrested 100 yards of the southwest slope from the enemy in a violent bayonet and grenade battle. The 3d Battalion, attacking with 2/382, managed to get a few men onto the reverse slopes of the hill, but murderous heavy machine-gun fire from Oboe Hill (also called 150 Meter Hill), 500 yards due south, completely covered the exposed terrain of Dick Hill in 3/382’s sector and effectively blocked the advance.

Fire from many of the same positions that had contained the advance of the 382d Infantry beat back the assault companies of the 307th on 16 May when the 77th Division renewed its attack on Flat Top and Chocolate Drop Hills. The 3d Battalion, led by tanks, made three attacks on Flat Top, reaching the crest each time only to be driven back by barrages of machine-gun and mortar fire. Attempts to flank Chocolate Drop were similarly stopped by bitter close-quarter combat and accurate long-range supporting fires. The reverse slope defenders of Chocolate Drop succeeded in pinning down the left flank of 2/307 driving toward Ishimmi Ridge, and the fire from the ridge held the right flank to moderate gains.

The 305th Infantry on 16 May concentrated its firepower in the attack zone of 3/305. Supported by armored flame-throwers and medium tanks mounting 105mm howitzers, the battalion advanced slowly along the finger ridges leading to the high ground of Shuri. The Japanese had turned the burial vaults that dotted the broken ground into mutually supporting strong points which could only be reduced by vicious close-in action. The day’s advance netted about 200 yards and brought 3/305 to within 500 yards of the northern outskirts of Shuri.

On 17 May the 77th Division surprised the Japanese with a very successful pre-dawn attack. Both assault regiments made substantial gains, and Chocolate Drop Hill fell to 3/307. Only on the extreme right of the division where 1/305 came under fire from 110 Meter Hill and the sprawling fortress houses of Shuri’s suburbs did the attack bog down. The 3d Battalion of the 305th and 2/307 dug in only a few hundred yards north of Shuri and Ishimmi in the highway valley. Flat Top was outflanked by 3/307, but heavy mortar and machine-gun fire drove back the assault companies when they tried to move into the exposed terrain south of the hill. The swift and silent advance had bypassed many enemy strong points and the daylight hours of 17 May were spent mopping up and sealing caves to secure the ground taken. Constant pressure was maintained along the new front line to keep the enemy off balance and consolidate forward positions.

The day’s attack had practically wiped out the Japanese 22d Regiment which had defended Chocolate Drop and still held the reverse slopes of FlatTop and Dick Hills with the help of the 1st Battalion, 32d Regiment. General Amamiya, 24th Division commander, issued orders on 17 May for the 32d Regiment to take over the defense of Shuri along a line from Ishimmi to Dick and Oboe Hills. The dwindling manpower available to both regiments was disposed in depth to contain any penetration and take advantage of the natural strength of Shuri’s eastern defenses.69

The 96th Division’s attack plan for 17 May called for the 382d Infantry to seize the hill mass south of Dick Hill that centered on Oboe Hill. The 2d Battalion cleaned up a host of fortified cave positions on Dick’s western and southern slopes, making a hotly-contested advance of 200 yards. The 3d Battalion, encountering heavy fire from Oboe Hill to the south and Love Hill to the east, pushed mop-up patrols into the high ground that led to the regiment’s objective. The intensity of enemy resistance met by the 382d indicated the need for further softening-up of the Oboe Hill area before a full-strength attack was renewed.

In the 383d Infantry’s zone of action strong tank-infantry patrols of 1/383 operated to the left front of the 382d Infantry to clean out some of the multitude of machine-gun and mortar positions that barred any advance to Love Hill. The 2d Battalion atop Conical Hill maintained steady pressure on the reverse slope defenses and gave up part of its extended front to the 381st Infantry during the day when the 96th Division committed a third regiment to the attack. While 2/381 continued its mop-up activities and patrolling along the coast, 3/381 took over the left of 2/383’s sector on the eastern slope of Conical Hill and brought forward its supporting weapons in preparation for an attack.

The following day 3/381 made the 96th Division’s main effort while the remainder of the assault battalions concentrated on mopping up the vicinity of their front lines with tank-infantry, flame-thrower, and demolition teams. Medium tanks operating to the west of the coastal road furnished excellent direct fire support against machine gun positions in the high ridge (Hogback Ridge) that extended south from Conical Hill. Despite this armored fire support, 3/381 was subjected to heavy and continual mortar and small-arms fire from Hogback, and its advance over the finger ridges that sloped down to the coast was limited to approximately 400 yards. Nevertheless, the battalion’s progress was encouraging and indicated the possibility of opening the coastal corridor for a drive through Yonabaru to outflank Shuri.

The 77th Infantry Division on 18 May drove its attack wedges farther into the inner core of Shuri defenses with 3/305 gaining 150 yards along the Ginowan-Shuri highway and 2/307 advancing as much as 300 yards toward Ishimmi. Resistance was fierce and unrelenting and the ground taken was won at a high cost in casualties. Enemy gunners on 110 Meter Hill, Ishimmi Ridge, and the reverse slopes of Flat Top and Dick Hills had good observation and fields of fire across the whole front of the division’s advance.

On 19 May the division undertook a systematic elimination of the enemy firing positions on the high ground to its front, using every available weapon for the task. The 306th Infantry, rested and partially rebuilt while it was in reserve, began moving up to replace the 305th, and 3/306 relieved 3/305 and portions of 2/307 along the low ground bordering the highway leading to Shuri. Small counterattacks, mounting in fury and strength as darkness approached, hit all along the 307th’s lines and were finally turned back at dawn on 20 May after all available artillery was brought to bear.

The 3d Battalion of the 381st Infantry again made the 96th Division’s main effort on 19 May while the 382d and 383d Infantry concentrated on destroying the cave positions and gun emplacements in the wildly irregular ground between Conical and Dick Hills. Prior to 3/381’s attack two platoons of medium tanks and six platoons of LVT(A)’s, plus artillery and infantry supporting weapons, bombarded Hogback Ridge and Sugar Hill which rose sharply at the ridge’s southern tip where it overlooked

Yonabaru. At 1100 the battalion attacked south and west toward Sugar Hill but gained very little ground in the face of the heavy defending fires. Numerous enemy positions spotted in the 18 May attack were destroyed, however, and the net result of the day’s action was a steady whittling down of the Japanese 89th Regiment’s defensive potential.

When 3/381 returned to the attack on 20 May, it made a slow, steady advance down the east slopes of Hogback, reaching the foot of Sugar Hill despite incessant grenade duels with the enemy fighting desperately to hold every inch of ground. The rest of the 96th Division also made significant gains as a result of three days of intensive preparatory firing and mopping up activities. The 1st and 2d Battalions of the 383d Infantry fought their way to jump-off positions within 300 yards of Love Hill and in the process destroyed enemy strong points that had blocked their forward progress for a week. The 382d Infantry supported a successful attack of the 77th Division on Flat Top Hill and finally reduced all enemy resistance on the south and east slopes of Dick Hill. The 3d Battalion of the 382d making its first all-out attempt to take Oboe Hill was forced to withdraw by mortar concentrations and grazing machine-gun fire that made its forward positions untenable. The 383d concentrated its efforts through most of 20 May on destroying newly located defenses.

The fire support furnished the 77th Division by 2/382, coupled with the morning-long battle fought by 3/307 for Flat Top Hill, spelled the end of effective resistance from the enemy strong point. The 307th Infantry had now knocked out the second of the three hill fortresses that faced it on 15 May and was ready to attack south to Ishimmi Ridge and Shuri. The 305th Infantry, with 1/305 and 3/306 in assault, coordinated its attack with the 1st Marines on its right and made a slow, grinding advance of 100-150 yards that brought it to within 200 yards of the outskirts of Shuri in the highway valley. To exploit the gains of 20 May General Bruce, his commanders, and staff planned a pre-dawn coordinated attack across the entire 77th Division front.

At 0415 on 21 May in the 305th Infantry’s

TANK DESTROYER of the 306th Infantry supports the attack of the 77th Division on Shuri. (Army Photograph)

sector 3/306 jumped off and advanced 200 yards without meeting any opposition. By 0520 the leading platoons had entered the northern suburbs of Shuri and were fighting on the eastern slopes of 110 Meter Hill. The relief of the 305th Infantry by the 306th was completed during the morning, and 2/306 moved into the division line on the right making visual contact with the 1st Marines. Much of the day was spent in mopping up bypassed enemy positions, and the regiment set up for night defense along a line from the forward slopes of Ishimmi Ridge through Shuri’s outskirts to 110 Meter Hill.

The pre-dawn attack of the 307th Infantry got off at 0300 when 1/307 passed through the lines of 3/307 and attacked toward the regiment’s next objective, three small hills which formed a triangle in the open ground 350 yards to the south of Flat Top. The leading company reached the objective at dawn but the enemy discovered the attackers and opened up with every type of weapon from the front and right flank pinning down the following units. No further progress was made, and at dusk the battalion dug in to hold its gains under continuous and accurate enemy fire.

The 96th Division made the most significant advances in the XXIV Corps zone on 21 May. The 1st Battalion of the 382d Infantry passed through the lines of 3/382 and advanced swiftly

Map 29

Penetration at Yonabaru

21-31 May 1945

against moderate opposition to Oboe Hill. The 2d Battalion on the right paralleled the advance, moving southwest over the open ground to a hill 400 yards from Shuri. At 1130 both units noted enemy troops withdrawing from their fronts towards the high ground at Shuri and fired on the retreating Japanese. A series of counterattacks by isolated enemy troops hitting all along the regimental front prevented any further advances during the day.

The Japanese defenders of Love Hill, who had blocked a week of incessant attempts by the 383d Infantry to advance southwest from Conical Hill, again succeeded in turning back the attack of 1/383. Although tank-infantry spearheads of the 1st Battalion reached the base of the hill, heavy and accurate artillery concentrations forced a withdrawal. Units on the right of 2/383 were also driven back by this artillery barrage, but the rest of the battalion, cooperating with the 381st Infantry’s attack, secured the western slopes of Hogback Ridge.

Fierce hand-to-hand combat cleared the eastern slopes of Hogback and brought 3/381 to the top of Sugar Hill by noon. Despite fanatical resistance which marked every foot of the day’s progress, the battalion drove its advance elements to positions within 200 yards of the Naha-Yonabaru highway. The success of 3/381’s attack on 21 May opened a 700-yard corridor down the east coast which promised to be the key to the reduction of the Shuri bastion. (See Map 23)

General Hodge, confident that the steady progress of the 96th Division would give him the chance to outflank Shuri, had moved the 7th Infantry Division to assembly areas just north of Conical Hill on 20 May. Before dawn on 22 May the 7th attacked toward Yonabaru and the high ground south of the village. The rain that had fallen intermittently throughout 21 May had increased to a steady, torrential downpour by the time the assault troops of the 7th were in position to jump off. In short order “the road to Yonabaru from the north–the only supply road from established bases in the 7th Division zone . . . became impassable to wheeled vehicles and within two or three days disappeared entirely and had to be abandoned.”70 Rain and mud, normally impartial signs of nature’s seasonal changes, became active and tremendously effective reinforcements for the Japanese Thirty-second Army.

Struggle in the Rain71

Paralleling the coast of Nakagusuku Wan between Yonabaru and the Chinen Peninsula was the forbidding Ozato hill mass,72 a tangled area of rugged peaks and ridges whose heights rivalled and surpassed those at Shuri. On the north the hill mass commanded the eastern end of the Naha-Yonabaru valley. Before the XXIV Corps could cut off the Japanese in Shuri by attacking west through the valley, it was imperative that strong blocking positions be seized in the Ozato hill mass to guard the left flank and rear of the assault force. The mission of the 7th Division’s 184th Infantry on 22 May was to capture Yonabaru and secure the heights that overlooked the valley and the village. (See Map 29)

Led by 2/184, the regiment moved out at 0200 from its positions at Gaja Ridge, passed swiftly and silently through Yonabaru, and by daylight had gained the crest of its first hill objective south of the village. Surprise was complete; at dawn the defenders of the hill were shot down as they emerged from their cave shelters to man entrenchments and gun positions. The Thirty-second Army had not expected an attack, still less a night attack, believing that the Americans would not advance without tank support.73

Capitalizing on its initial advantage, the 184th Infantry committed 3/184 on the right of the 2d Battalion and drove forward to seize the key points of the terrain. Despite the rain

105MM HOWITZER of the 15th Marines is almost swamped, but still in firing order, after ten days of rain.

and mud which severely hampered supply operations and curtailed the effectiveness of supporting weapons, the regiment advanced 1,400 yards during the day and set up secure night positions holding most of the ground on its assigned objectives.

On the opposite flank of the Tenth Army front on 22 May the 4th Marines attacked to bring its lines up to the Asato Gawa. While 2/4 held its position on Half Moon Hill and maintained contact with the 1st Division, 1/4 and 3/4 slogged slowly through the “gooey slick mud”74 to the bank of the rain-swollen river. Enemy opposition was sporadic and ineffective, and assault troops seized their objective by 1230. Patrols immediately crossed the Asato and advanced 200 yards into the outskirts of Naha before drawing scattered enemy fire. The troops dug in along the north bank of the river for night defense while tentative plans were laid for a crossing in force on 23 May. (See Map 30)

In sharp contrast to the sweeping advance of the 7th Infantry Division and the encouraging progress of the 6th Marine Division was the situation in the center of the Tenth Army front. For the 1st, 77th, and 96th Divisions 22 May marked the beginning of a week of bitter frustration and fruitless pounding against the Shuri defenses. Deprived of vital tank support by the mud which blanketed the zone of attack, the infantrymen of the three divisions could do little more than probe and patrol to the front. Small local gains were made each day and relentless pressure was maintained against the defenses of the enemy fortress city; but each time a full-scale coordinated attack was planned, a fresh onslaught of driving rain cancelled the operation.

The floor of every draw and gulley became a sticky morass of knee- and thigh-deep mud while the precipitous slopes of the hills and ridges,

Map 30

Capture of Naha

21-31 May 1945

treacherous footing under the best conditions, were virtually unassailable. Every ration box, water can, and round of ammunition needed to maintain the assault troops had to be manhandled up to the front lines when lowering skies prevented air drops. Reserve units, depleted from days of heavy fighting for Shuri’s heights, had to provide many of the necessary carrying parties. Every type of vehicle, including LVT’s and wide-tracked bulldozers, eventually bogged down in the mud, and the gap between forward supply dumps and the battle line steadily widened despite day and night efforts by engineers to maintain the vanishing road net. Under these conditions it was impossible to build up adequate supply reserves which would be needed to sustain an all-out assault. Day after wearying day the sodden infantrymen left their flooded foxholes to attack the Japanese positions, sometimes gaining, sometimes losing a small patch of ground, but the net result was stalemate.

Aided by the fact that their open seaward flanks gave them a route of supply denied to units in the center of the Tenth Army’s front, the 6th Marine and 7th Infantry Divisions drove back the Japanese who held the coastal flats. Once their direction of attack shifted toward Shuri’s heights, however, they encountered the same fierce resistance met by the 1st, 77th, and 96th Divisions. This opposition, coupled with the continued bad weather, was enough to lose the “opportunity to isolate completely the main enemy force in Shuri.”75

On 23 May the enemy Thirty-second Army served notice on the 7th Infantry Division that a drive west through the Naha-Yonabaru valley would be bitterly opposed. While the 184th Infantry with its 2d and 3d Battalions in assault drove further into the Ozato hill mass securing the mouth of the valley, the 32d Infantry moved through Yonabaru and struck west and southwest to cut off the defenders of Shuri. Enemy opposition increased steadily during the day with mortar and machine-gun fire coming from a series of low hills to the front near Yonawa. The tanks which had been counted upon to exploit the breakthrough were immobilized by the mud of the flooded valley, and 2/32 and 3/32 were forced to dig in along a line a mile to the southwest of Yonabaru.

During the night of 22-23 May a patrol from the 6th Reconnaissance Company scouted the south bank of the upper reaches of the Asato Gawa. Returning through the lines of 1/22 the patrol reported:

Reconnaissance conducted successfully. Stream fordable at low tide. Routes steep but will accommodate infantry. Covered half of bluff on south side of river. No occupied emplacements found. Met 2 Nip patrols 1-6 man, 1-3 man. Japs threw grenades. Killed 1.76

Since the night reconnaissance indicated to General Shepherd that “it might be feasible to attempt a crossing of the Asato without tank support,”77 he ordered the 4th Marines to intensify its patrol activities south of the river during the early morning of the 23d. If resistance proved light, the regiment was to be prepared to execute the Asato crossing. The patrols received long-range machine-gun fire from high ground around Machisi, but there was little evidence of determined resistance at the river’s edge.

At 1000 General Shepherd made the decision to force the Asato line, and at 1030 Companies A and B of 1/4 and I and L of 3/4 began wading the stream. By 1100 a firm bridgehead had been secured on the south bank.78 The day’s objective was a low east-west ridge 500 yards south of the river, and resistance increased sharply as the assault troops approached it. Many Okinawan tombs on the forward face of the ridge had been fortified, and the reverse slopes were studded with mortar positions. The heavy fire slowed the advance to a crawl, and the troops dug in on the ridge approaches as darkness fell.

At the time of the assault crossing the Asato had been ankle deep,79 but a steady driving rain turned the stream into a chest-high torrent. While engineers struggled to put in a bridge

under intense artillery and mortar fire, men stood for hours in the water forming a human chain to pass supplies and casualties between the muddy banks.80 Two foot bridges had been constructed by midnight, but attempts to bring up materials for a Bailey bridge during the afternoon were beaten back by accurate enemy artillery fire.81

General Geiger shifted the boundary of the 1st Division to the right during the morning of 23 May so that 2/4 could close up its extended lines and better protect the left flank and rear of the 4th Marines’ bridgehead. The 5th Marines on the right of the 1st Division committed 3/5 to take over the extended front. No forward progress was made by either assault regiment of the 1st Division although combat patrols rooted out the enemy defenders in the vicinity of the front lines. The 77th and 96th Divisions also limited their activities to patrolling and mopping up near the positions they had reached on 21 May.