CHAPTER 8

IIIAC Enters the Lists

The steady attrition of the XXIV Corps drive to the south was reflected in mounting Japanese casualty figures. By the end of April the 62d Division, which bore the brunt of the early fighting, had been reduced to less than half its original combat strength. Many officers of the Thirty-second Army, although pessimistic regarding the chances of eventual Japanese victory on Okinawa, were encouraged by a significant fact. They considered it to be “an unprecedented occurrence since the start of the Pacific War that after thirty consecutive days of systematic fighting the main body of one of [their] fighting forces should remain intact.”1 Most of the units of the 24th Division, 44th IMB, and 5th Artillery Command were as yet untouched by the fury of the battle for the Shuri defenses. The sentiment at enemy headquarters was overwhelmingly in favor of committing these fresh troops en masse in a concerted effort to stop the American advance.

Japanese Counterattack2

The fear of an American landing at Minatoga dominated Thirty-second Army planning during early April; in fact, the army staff decided that “such a landing could be executed relatively safely and easily, and, moreover, it would bring a prompt ending to the fighting.”3 The Japanese officers felt that successful exploitation of a beachhead south of Shuri would enable General Buckner’s men to cut the Thirty-second Army in two and defeat it in detail.

By 20 April it was apparent to both sides that the overextended 62d Division could not hold its lines much longer without substantial reinforcement. If the Thirty-second Army persisted in keeping the majority of its troops positioned below the Naha-Yonabaru valley to meet a threatened American landing, that could only lead to the swift collapse of the Shuri defenses. So the Japanese made a reappraisal of their objectives. Since General Ushijima’s mission was to prolong the battle and inflict the heaviest casualties possible, he decided to concentrate theThirty-second Army in defense of the strongest position on Okinawa–the Shuri bastion.

Consequently, orders were issued to the 24th Division and the 44th IMB to begin moving north on 22 April. The 24th Division was to recover control of its 22d Regiment from the 62d Divisionand take over the right sector of the defensive position, occupying a line from Gaja on the east coast to Maeda at the eastern end of the Urasoe-Mura Escarpment. The 62d Division’sshattered battalions were to concentrate

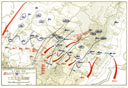

Map 22

Japanese Counteroffensive

4-5 May 1945

in the area from Maeda to the west coast near Gusukuma. Backing up the 62d from positions on the high ground to the south and east of the Asa Kawa, the 44th IMB would cover Naha and the ridges and draws on Shuri’s western flank.

The area below the Naha-Yonabaru valley was not to be completely denuded of Japanese troops. Admiral Ota’s naval force was still charged with the defense of Oroku Peninsula, and a makeshift guard organization formed from miscellaneous artillery, engineer, service, and supply elements was assigned to protect the Chinen Peninsula area. Should the Americans attempt a landing, the orders to Army troops were to make a fighting withdrawal to Shuri where the battle would be continued to the death of the last defender.

By 27 April the 24th Division had completed movement to its sector north and east of Shuri, and the 44th IMB was in position below the Asa Kawa. The steady advance of XXIV Corps assault battalions was continuing despite the infusion of new strength into the Japanese front line. On the west coast near Machinato airfield and in the center at Maeda and Kochi, the defending troops were gradually pushed back as small, local counterattacks failed to regain lost ground. At Thirty-second Army headquarters below Shuri Castle the proponents of aggressive action, led by General Cho, were able to convince General Ushijima that the time was ripe to use the relatively intact 24th Division as the spearhead of an all-out Army counterattack. There was one lone dissenter to this plan, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara, senior staff officer and operations chief.

The colonel pointed out that “to take the offensive with inferior forces against absolutely superior enemy forces is reckless and would only lead to certain defeat.” He noted further that the Japanese would have to attack the Americans in positions on commanding ground, making it “more and more definite that the offensive would end in failure.” Yahara maintained that the only sensible course in keeping with the army’s mission was the continuation of:

. . . its current operation, calmly recognizing its final destiny–for annihilation is inevitable no matter what is done–and maintain to the bitter end the principle of a strategic holding action. If we should fail, the period of maintaining a strategic holding action as well as the holding action for the decisive battle for the homeland would be shortened. Moreover, our forces would inflict but small losses on the enemy; while on the other hand, scores of thousands of our troops would be sacrificed in vain as victims of the offensive.4

Although Colonel Yahara strove desperately to make his views prevail, General Cho, backed by the division and brigade commanders, won the decision. The plan of attack that evolved was exceedingly ambitious. Its aim was the destruction of the XXIV Corps and its ultimate objective the area around Futema which the Japanese believed to be the location of Tenth Army headquarters.5

The day of attack (X-Day) was tentatively set as 4 May and the hour (Y-Hour) as 0500. The24th Division was to make the initial assault with three regiments abreast. On the east, the 89th Regiment attacking at Y-Hour was to penetrate the front of the U.S. 7th Division and advance to the hills near Minami-Uebaru by sunset. In the center, the 22d Regiment was to hold its positions near Onaga and Kochi and support the attack of flanking units by fire. When the Japanese attack reached an east-west line through Tanabaru, the 22d was to move out, destroy the American units to its front, and follow up the assault in the center rear of the advancing units. On the west of the 24th Division zone, the 32d Regiment, making the division’s main effort, would drive forward at Y-Hour, seize the U.S. 77th Division’s positions southeast of Maeda, and take the heights west of Tanabaru by sundown on X-Day. (See Map 22,)

The 27th Tank Regiment, moving from positions near Ishimmi, was to penetrate the 77th Division’s lines to the west of Kochi and support in turn the attacks of the 32d and 22d Regiments. The 44th IMB was to shift to the area northeast of Shuri on 3 May ready to follow the attack of the 32d Regiment by an advance to the west coast at Oyama. The brigade was then to turn south isolating the 1st Marine

Division and annihilating it with the help of the 62d Division, the only major Japanese unit not committed to the attack.

The full power of General Wada’s 5th Artillery Command was assigned to support the assault. During the night of 3-4 May the guns, mortars, and howitzers were to move out of their hidden firing positions into the open where they would be free to use maximum elevation and traverse. Even the naval base force was to play its part. Admiral Ota was directed to form four “crack” infantry battalions as an exploitation reserve to be committed on Thirty-second Army order.

The open flanks of the XXIV Corps position were not forgotten in the Japanese attack plan. The main strength of the 26th Shipping Engineer Regiment, using a miscellany of landing barges, small boats, and native canoes, was to embark at Naha on the night of 3-4 May and land behind the 1st Marine Division front at Oyama. At the same time elements of the 26th, 28th, and 29th Sea Raiding Squadrons were to bypass the Marine lines by wading the reef and move inland in support of the counterlanding. In all about 700 men were committed to the west coast attack. On the east coast, the same plan was to be followed with approximately 500 men from 23d Shipping Engineer Regiment and 27th Sea Raiding Squadron attempting to come ashore at Tsuwa behind the 7th Division’s front lines.

Both regiments were to infiltrate American rear areas in small groups using grenades and demolition charges to destroy equipment and harass command posts. The raiders were not to make a concerted attack unless they had at least 100 men together. If all went well the two units were to join up near the center of the island and assist the 24th Division’s advance.6 TheThirty-second Army was able to get air support from Japan and Formosa for its proposed attack. Starting at dusk on 3 May, flights of enemy bombers from Kyushu were slated to hit Yontan and Kadena airfields in an attempt at catching TAF planes on the ground. After this preliminary air raid, the fifth major Kamikaze attack in less than a month was to be made on the support vessels of TF 51.

Although both Tenth Army and XXIV Corps considered a full scale counterattack to be a definite enemy capability, the weight of evidence on the evening of 3 May favored a delaying action from successive positions with the Japanese “defending each position until the troops on the position are nearly annihilated.”7 Elements of the infantry regiments of the 24th Division had been identified as part of the enemy force opposing the 7th and 77th Divisions, but there were no indications that a major attack was imminent. No particular significance was attached to the determined attempts of the 32d Regiment and the 62d Division to regain the commanding heights at the eastern end of the Urasoe-Mura Escarpment. Local counterattacks to retake lost ground had been part of the enemy defensive pattern since L-Day, and the stiffened nature of Japanese resistance was easily attributed to the presence of fresh troops in the front lines. The Japanese were successful in masking their counterattack preparations, but the XXIV Corps was alert and ready to handle the assault when it came.

At 1800 on 3 May enemy planes approaching Okinawa from the direction of Formosa made the first attack of a two-day struggle which Colonel Yahara called “the decisive action of the campaign.”8 For more than two hours Marine and Navy pilots and antiaircraft gunners, afloat and ashore, fought off a determined assault, downing 36 planes.9 The enemy bombers, harassed by AA fire, unloaded at high altitudes over Yontan airfield and the Hagushi anchorage causing only superficial damage. It was a different story with the Kamikaze pilots whose will to die drove them through a wall of shell fragments and explosions toward their favorite targets, the picket ships. The destroyer Little and LSM 195 were sunk; two mine layers and an LCS were damaged.10

Shortly after midnight the first of an estimated

60 enemy bombers began attacking Tenth Army rear areas. Again AA fire kept the planes high and the bombing erratic. The only serious damage was suffered by IIIAC Evacuation Hospital No. 3 near Sobe where a string of bombs demolished two dug-in surgery wards, killing 13 and wounding 36.11 The use of “window” by the attacking enemy planes prevented radar-directed TAF night fighters from closing with the bombers.12

With daylight the Kamikazes resumed the attack, timing their approach to coincide with Thirty-second Army assaults ashore. From 0600 to 1000 the suicide pilots attempted to reach the Hagushi anchorage; only one succeeded and he crashed into a turret on the cruiser Birmingham,leaving 25 dead, 60 wounded, and 17 missing in his wake. On the picket line losses and damage again were heavy. Two destroyers, Luce and Morrison, and two LSM’s went to the bottom; two more destroyers, a mine sweeper, and an LCS were damaged. In addition the light mine layerShea was hit by a baka bomb13 and suffered severe fire damage and flooding, with 25 men reported killed.

Early in the evening of 4 May, suicide planes made another attack, this time striking the escort carrier group of TF 51. A Kamikaze plunged right through the flight deck of the Sangamon, and the resultant explosion damaged both elevators and destroyed 21 planes. The toll of Japanese planes downed on 4 May reached 95 as this last attack subsided. But the cost in naval casualties was also impressive: 91 KIA, 280 WIA, and 283 MIA.14

The Navy’s contribution to the repulse of the coordinated Japanese attack was not confined to beating off aerial assaults. Cruisers, destroyers, and gunboats on “flycatcher”15 duty off both coasts discovered the attempts of the shipping engineer regiments to slip behind American lines and aided ground forces with illumination and gunfire in meeting the counterlandings. When the full strength of the Japanese attack revealed itself at dawn on 4 May, the NGF force assigned to XXIV Corps for daylight support, two battleships, five cruisers, and eight destroyers, joined with artillery and air to smash the advancing infantry and silence enemy supporting weapons.

Japanese artillery had begun firing with darkness on 3 May and as the night wore on the volume of fire steadily increased with shells falling mainly on the forward positions of the 7th and 77th Divisions. A regular gun duel ensued as American artillery battalions replied.

On the quiet sector of the front shortly after 0100, LVT(A) crews guarding the shore near Machinato airfield opened up on unidentified persons they heard on the beach. Naval support craft were soon observed directing low angle fire at targets in the water just offshore.16 Less than an hour after this initial outbreak of firing the 1st Marines reported enemy barges heading in for shore at Kuwan.

The landing craft, which carried the bulk of the attacking forces, had had trouble with the reefs and lost their way.17 Instead of reaching their objective, Oyama, well in the rear of Marine lines, the Japanese turned shoreward at the exact point where Company B of 1/1 had anchored its night defense position. The stealthy approach was undetected by beach sentries until the enemy set up a terrific din of screeching battle cries that revealed their presence.

WOUNDED MARINES are placed in the shelter of an LVT while mopping-up operations proceed against survivors of the Japanese counterlanding. (Navy photograph)

It was all the warning the Marines needed.

Mortars and heavy machine guns sited to cover the reef began firing at the crowded barges, some of which carried as many as a hundred men. Rifle grenadiers from the defending platoon of Company C (attached to Company B) which held the extreme right flank of the 1st Battalion’s line found targets in the open boats. Soon a weird half-light from flares, tracers, and burning barges suffused the area. Riflemen and machine gunners fired at bobbing heads in the water and raked the reef to stop the determined attackers.18

Reinforcements had been dispatched by Colonel Chappell as soon as word of the attack was received. The 2d Battalion, in regimental reserve, sent Company E to close on the right flank of the Company C platoon. LVT(A)’s from the 3d Provisional Armored Amphibian Battalion helped to seal off the landing area by taking up positions on the reef above Kuwan. By 0245 the ring of fire was complete and the Japanese survivors on the beach were being steadily pounded by all available weapons.

Some of the first enemy troops to get ashore had been able to infiltrate into the rear of 1/1’s lines before the trap was sprung. Company F, holding the right flank forward of Company B’s position, engaged these raiders in an intense fire fight that ended with 75 enemy dead lying scattered in and around the Marines’ positions.19

After the dispatch of Company E to Kuwan to contain the enemy attack, Colonel Chappell was left with one rifle company (G) as regimental reserve. The uncertainty of the situation prompted him to request the attachment of a battalion of the 7th Marines to his regiment. Division approved his request, and at 0300 2/7 began moving south through moderate enemy shelling to report to 1/1 for orders. Lieutenant Colonel Berger and his S-3 preceded the unit and at 0500 arrived at the 1st Battalion command post. The situation was well in hand. Except for scattered enemy groups hiding out in Kuwan, the bulk of the 300-400 who had attempted the main landing were dead, sprawled on the beach along the seawall or aimlessly floating amid the gutted hulks of their landing craft. At 0645, 2/7 was given the mission of mopping up the counterlanding area and began relieving the right flank elements of 1/1 so that the 1st Battalion’s attack to the south could continue.20

The landing at Kuwan was not the only one attempted behind the 1st Division front that night. Scattered small enemy groups, most using native canoes, were able to get ashore farther up the coast, an estimated 65 landing near

Isa in the vicinity of the division command post. The more usual fate of the attackers was to die in the water as the combined fire of naval vessels, LVT(A)’s, infantry, and service troops caught their boats before they could make the beach. Those few score Japanese able to reach shore were doomed with the coming of daylight to be hunted down and killed. A carrier pigeon found in the possession of one of the raiding groups was released to carry back a message to enemy headquarters that said: “We are returning your pigeon. Sorry we can not return your demolition engineers.”21

At approximately the same time the 26th Shipping Engineers were attempting to wreak havoc behind the Marine front, the 23d Regiment attempted to put its boats ashore in the 7th Infantry Division zone. Naval patrol vessels spotted the attempt, illuminated the area with star shells, and opened fire. On shore the 7th Division Reconnaissance Troop, guarding the Yonabaru airfield area, cut loose with all its firepower and joined the naval craft in completely destroying the attack. Only an estimated 20 men were able to get to the beach and these were soon eliminated. Those lucky few engineers whose boats escaped the holocaust turned back to their starting points, leaving behind some 400 dead.22 With the defeat of counterlanding attempts on both coasts, the flanks of XXIV Corps were secure, and the opening move of the Thirty-second Army ground attack had ended in abject failure.

The steady fury of enemy artillery fire reached a screaming crescendo at 0430 when the Japanese began a half-hour preparation for the 24th Division’s attack. More than 7,600 rounds were fired in the preparatory phase, and 5th Artillery Command’s guns hurled 8,600 more during the course of the day’s action.23 In addition, many thousands of mortar rounds fell on the front lines as attacking troops sought to penetrate XXIV Corps defenses.

In the gray light of dawn the 24th Division’s assault units moved forward through their own supporting fire, taking heavy casualties in order to reach the American lines. Most of the company- and battalion-sized attacks died aborning in the smother of destruction laid down by NGF, air, and 16 battalions of division artillery, backed up by corps artillery’s 12 battalions of 155mm guns and 155mm and 8-inch howitzers. With daylight the first of 134 planes to fly supporting missions for XXIV Corps on 4 May made its initial bombing run. By 1900, 77 tons of bombs, 450 rockets, and 22,900 rounds of machine-gun and cannon fire had been expended on Japaneses troop concentrations and artillery positions.24 Despite the fact that the area was under heavy enemy air attack, NGF support vessels, whose power ranged from the 14-inch rifles of theNew York and Colorado25 to the mortars and 20mms of the ubiquitous support craft, ranged the coastal waters delivering observed and called fires on enemy targets.

Because Thirty-second Army had directed that a heavy screen of smoke be laid on American lines to cover the Japanese advance, staff observers on the heights of Shuri could not see the progress of their battle. However, “good news” had poured into the army command post at the start of the attack telling of “the success of the offensive carried out by the 24th Division.“26Unfortunately for the Japanese, the overly imaginative reports of assault commanders did not reflect the true situation.

On the east coast, the initial attack of the 89th Regiment was repulsed by 7th Division defenders, and all subsequent attempts by the enemy unit to reorganize and renew its advance were prevented by the storm of supporting fire that covered assembly areas and routes of approach. By noon the threat of attack was gone, and front line regiments were mopping up the scattered and demoralized elements of the 89th that had penetrated to the American positions.

In the center of the line the Japanese 22d Regiment was never able to fulfill its role of following up the “successful” advance of flank

units, and the regiment spent the day locked in a violent fire fight with men of 3/306, 3/17, and 1/17 holding the Kochi-Onaga area. The Japanese reported the 22d “was not able attain results worth mentioning.”27

The highest hopes and greatest strength of the 24th Division were centered in the 32d Regiment’s attempt to gain control of the escarpment near Maeda, thus breaching the 77th Division’s lines and opening a hole through which the waiting 44th IMB could pour into the 1st Marine Division’s rear area. The 1st and 3d Battalions of the 306th Infantry, holding the left of the 77th lines, turned back the first tank-led assaults launched by the 32d Regiment. Rebuffed in this attempt to gain the high ground flanking the central island corridor leading to Futema, the Japanese concentrated their efforts on driving the 307th Infantry off the top of the Urasoe-Mura Escarpment.

A day-long succession of strong enemy counterattacks hit all along the front of 307th as the regiment attempted to gain the south slopes of the hill mass. Attackers and defenders, often locked in hand-to-hand combat, seesawed back and forth over the ridge crest, but the constant pounding of supporting weapons whittled the strength of the 32d Regiment down, and nightfall found all three battalions of the 307th firmly dug-in on the south slope of the escarpment. The major effort of the Japanese counterattack had failed and XXIV Corps could report that its troops had either securely held their original positions or taken more enemy ground on 4 May.

The farthest advance of XXIV Corps during the day’s action was made in the 1st Division zone. The time of the Marines’ morning attack had been successively delayed from 0800 to 0900 to 1000 while unit reorganization and ammunition replenishment necessitated by the counterlanding attempt took place. When the assault battalions of the 1st and 5th Marines moved out, they were hit immediately by heavy fire from well-integrated defensive positions of the Japanese 62d Division.

Company F attacking on the right of 1/1 was soon pinned down in the ruins of Jichaku, and Company A, which attempted to bypass the village, was stopped by murderous fire coming from a defile in a ridge to its front. Japanese heavy machine guns emplaced in the ruins of a sugar mill on the south bank of the Asa Kawa had a clear field of fire through the gap, which was itself strongly defended by dug-in enemy positions. Lieutenant Colonel Murray, noting the moderate opposition on his left where 3/1 was advancing, decided to exploit the weak flank of the gap position.

At 1600 Company C in assault with B following immediately to the rear crossed the low ground to the right of 3/1 and drove to the heights overlooking the left of the defile and the river to the front. Casualties were surprisingly light and the two companies dug in for the night in firm possession of their attack objective. Except for a short stretch of enemy ground from the gap to the eastern edge of Jichaku, the 1st Battalion was only a few hundred yards from its final objective, the north bank of the Asa Kawa.28

Lieutenant Colonel Sabol’s 3d Battalion had not had an easy time of it on 4 May, but the commander was able to keep the positions won by his forward elements. Company I on the right flank moved out at 1000 and gained a hold on a ridge 300-400 yards to its front where it was exposed to damaging enemy fire from three sides. The steady drain of casualties was slowed by noon as Companies K and C came up on either flank and took the defending positions under fire. With Company L keeping pace with the 5th Marines’ flank in that regiment’s eastward drive, a gap quickly opened between it and Companies K and I. Late in the afternoon, the 2d Battalion (less Company F) was moved to a blocking position south of Yafusu to cover this space and stop any enemy breakthrough attempt.29 Although all three of its battalions were now committed to hold the ever-widening regimental front, the 1st Marines had a sure grasp on the ground taken during the day’s advance.

In the 5th Marines’ zone, 2/5, holding the high ground on the 77th Division boundary, remained in position during the day’s action and

supported the advance of 3/307 and 1/5 on its flanks. Lieutenant Colonel Shelburne’s 1st Battalion pivoted on 2/5 and its own left company and swung its right through 400 yards of hotly-contested broken ground during the day. On the right of the regimental zone 3/5 continued the plan of cutting off the strong enemy pocket in the gorge forward of Awacha and pushed Company L on its left up to tie in with the right of 1/5. Company I, moving forward about 250 yards along the battalion boundary, kept pace with the advance of 3/1. By early afternoon the 3d Battalion’s front, moving both south and southeast, had stretched very thin, and a sizeable hole had developed between Companies L and I. At 1500, division attached 3/7 to the 5th Marines and Colonel Griebel moved the battalion to a blocking position behind 3/5. In order to strengthen the lines for night defense, Company K of 3/7 was committed to cover the gap.

An aura of gloom pervaded the Japanese Thirty-second Army command post on the evening of 4 May. It was obvious to even the most rabid fire-breathers that the ground offensive had failed. But hope dies hard, and General Amamiya, commanding the 24th Division, ordered the 32d Regiment to try again under cover of darkness what it had failed to do during the day. At 0200 on 5 May, following a heavy mortar and artillery barrage, the regiment smashed into the front lines of the 77th Division, attempting to penetrate the positions of the 306th Infantry. American artillery broke up this effort, but the enemy returned to the attack at dawn, this time led by tanks. Again the assault was stopped, six tanks were knocked out, and the remnants of the 32dforced to withdraw. The 3d Battalion had been badly mauled, the 2d wiped out,30 and the 1st,although it scored an initial success, was doomed to the same fate.

In the confusion of the counterattacks a substantial portion of 1/32 was able to infiltrate the 77th Division’s lines on the east side of the Ginowan road. Moving cross-country in column, the enemy battalion retook Tanabaru and established a defensive position on the escarpment to the northeast of the village where it was joined by other scattered infiltrating groups that had been able to slip through the lines on 4 May.

The task of reducing this strong point, which was just within the 7th Division’s zone, fell to the 17th Infantry’s reserve battalion, 2/17. A dogged battle was fought behind the lines for three days before the last of more than 400 enemy troops was eliminated. Some elements of 1/32,led by the battalion commander, managed to escape the Tanabaru death trap and return to the Shuri lines. General Ushijima commended the skeletal battalion for its “success” behind the American lines, but the gesture was a hollow one.

The Thirty-second Army needed such a morale boost, however empty or futile it may have been. One Japanese platoon leader, probably a member of the 15th IMR, noted in his diary on 6 May that “there’s an unsavory rumor current that the situation at the front is critical.”31 The actions of 5 May may well have prompted his concern. Taking advantage of the dazed condition of enemy 24th Division units, the 7th and 77th Infantry Divisions had sent strong patrols into the counterattack area to mop up enemy remnants and count the numerous bodies left in the wake of American air, NGF, and artillery defending fires. Survivors of the various counterattacks were relentlessly hunted down while the Army divisions consolidated their positions and prepared for further advances. Only in the 1st Marine Division area was the pattern of resistance the same as it had been before the counterattack started.

Made even more desperate by the failure of the 24th Division’s grand attack, the rag-tag battalions of the 62d Division made every yard of advance count in Marine lives. Concentrating their strength on the left of the 1st Division zone, the defenders fought to the death to guard the vital western approaches to Shuri. Each pillbox, cave, and tomb was the center of a storm of fire that hit attacking platoons from

all sides. Despite this desperate resistance, the Marines were able to make substantial progress during the day.

The 5th Marines advanced its lines an average of 300 yards in the center and on the left, with 1/5 making the main effort. The battalion, attacking at 0730 with the support of 15 gun and two flame tanks,32 managed to gain the nose of the high ground stretching west from Awacha before it was stopped by enfilade fire from both flanks. On the left, 2/5 moving through a deluge of enemy artillery fire, had made 250 yards, guiding its advance on 3/307 which was mopping up the reverse slopes of the escarpment. On the right, 3/5 had made no appreciable forward progress but had spent the day cleaning up the complex of enemy defenses in the vicinity of its night defense position. At dusk the regiment tied in solidly across its front, faced with the prospect of another day’s painful advance into the fire lanes and impact areas of the enemy’s Awacha defenses.

In the 1st Marines’ zone the attack got off at 0800 with 2/1 moving through the 3d Battalion and advancing with 1/1 toward the Asa Kawa. By 1123 the 1st Battalion, with five rifle companies under its command (A, B, C, F, and I), had seized the high ground along the river to its center front against light resistance. Pockets of enemy on both flanks were destroyed during the afternoon, and by evening the battalion was dug in on commanding ground along the river line. The 2d Battalion, which had met much heavier enemy fire coming from its front and the village of Asa to the southwest, progressed slowly during the day. At 1600, Lieutenant Colonel Magee ordered his men to begin preparing strong night defenses to hold the ground between 3/5 and 1/1. Company L of 3/1 was positioned on high ground to the 2d Battalion’s rear to cover any gaps in the line, and at 1735 Company F was released from attachment to 1/1 and moved to defensive positions in the vicinity of 2/1’s command post. Although the 1st Division was ready for a renewal of the enemy counterattack in its zone, the night passed quietly.

A recapitulation of the cost of the two days’ action in XXIV Corps zone showed that the 7th and 77th Divisions, which had blunted the full force of enemy counterattack, had lost 714 soldiers killed, wounded, and missing in action, while the 1st Division which had continued its drive to the south had taken corresponding losses of 649 Marines.33

It was the Japanese, however, who had taken the significant losses during the counterattack period. XXIV Corps counted 6,227 enemy dead, almost all of whom were irreplaceable veteran infantrymen. In addition to loss of men and equipment in the front lines, the enemy had 59 artillery pieces destroyed during the short time they were set up in open positions by the American air-NGF-artillery team. Tenth Army troops were never again to encounter artillery fire as heavy or as destructive as that which had covered the Japanese assault.

Colonel Yahara, who had vehemently opposed wasting men and matériel in an operation that had no chance of success, was vindicated in his prediction of the utter failure of the enemy counterattack. He won a tearful promise from General Ushijima that the army would follow Yahara’s counsel in the future. The pattern of defense in the 62d Division zone was to be reinstituted across the entire enemy front. The 24th Division and 5th Artillery Command were directed to reorganize and shift to a holding action designed to bleed American strength by forcing the Tenth Army to continue its slow, deadly, yard-by-yard advance into the fire of prepared positions.

The definitive estimate of the value of the Japanese counterattack in the defense of Okinawa was furnished by its prime motivator, General Cho. “After this ill-starred action,” the fiery Thirty-second Army chief of staff was reliably reported to have “abandoned all hope of a successful outcome of the operation and declared that only time intervened between defeat and the 32d Army.“34

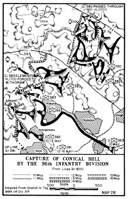

Map 23

Tenth Army Progress

5-21 May 1945

The Battle Lines Are Drawn35

On 6 May Tenth Army subordinate units received Operation Order 7-45 which marked the beginning of a full strength drive to destroy the enemy’s Shuri bastion. At 0600 on 7 May General Geiger was directed to take command of the 1st Marine Division’s portion of the XXIV Corps front. At the same time General Buckner would assume direct tactical control of the two-corps attack. Geiger was further ordered to move the 6th Marine Division south from its concentration points near Chibana to take over the right of the 1st Division’s zone of action. In preparation for a coordinated army assault, IIIAC and XXIV Corps were directed to advance and seize a jump-off line running generally east from Asa through Dakeshi to a road junction 1,000 yards northeast of Shuri and then southeast to the outskirts of Gaja. (See Map 23)

On 6 May action in the 7th Division’s zone was limited to aggressive patrolling in strength to develop the approaches to Conical Hill and wipe out the scattered remnants of the abortive Japanese counterattack. In the center of the XXIV Corps front the 77th Division during the night of 5-6 May smashed the last enemy effort to maintain a hold on the Urasoe-Mura Escarpment. Both the 306th and 307th Infantry beat back infiltration attempts, and 3/307 counted 250 enemy dead in front of its lines after repulsing a savage counterattack. Capitalizing on the severe losses it had inflicted on the Japanese defenders, the 307th, with 3/305 and 3/307 in assault, drove 800 yards down the division boundary during the day to lock its hold on the south slope of the escarpment. Cost of the bitter seven-day contest for the dominant high ground north of Shuri had been high to both sides, and “in the most severe fighting any of the troops had ever experienced,”36 the 77th Division had lost 197 men killed in action, while the enemy left behind more than 17 times as many–an estimated 3,417 dead.

Along the west coast, while preliminary plans were drafted for the movement of the 6th Marine Division into the front lines, the attack of the 1st Division on the Dakeshi-Awacha hill complex continued. The 7th Marines took over the right coastal flank of the division’s line at 0730 when 2/7 relieved 1/1. At 0900 the 2d Battalion’s left flank assault units attacked behind an artillery and NGF preparation to complete the seizure of the north bank of the Asa Kawa. Within 45 minutes Lieutenant Colonel Berger’s men had advanced 400 yards to their objective and begun to dig in. Regimental and battalion supporting weapons were moved up to silence the enemy artillery, mortars, and machine guns firing from the hills across the estuary.

The new regimental boundaries narrowed the attack zone of the 1st Marines considerably and enabled the assault battalion commanders to concentrate their forces against the western approaches to the Dakeshi hill defenses. Concentration of power was urgently needed since the front line in the 1st Marines’ area cut back sharply from the Asa Kawa to the positions of the 5th Marines north of the Awacha Pocket. Attacking units were subject to brutal frontal and flanking fire from a 1,000-yard-long maze of heavily organized hills and ridges that guarded Dakeshi’s western flank.

When Lieutenant Colonel Sabol’s 3d Battalion, with Companies I and L in assault, attacked to the south, the Japanese defenders from the 62d Division smashed the attempt handily. The enemy permitted Company I to reach its objective and then pinpointed the exposed assault platoons with a hail of machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire. Although the men attempted to dig in, the effort was unsuccessful and the company withdrew under a continuous barrage of mortar fire.37

In 2/1’s zone the story was much the same. Company F moved through the lines of

Company L at 0945 and attacked west toward Hill 60 which commanded the battalion front. Tanks and assault guns accompanied the infantry, blasting caves and pillboxes to clear the path. A well-concealed enemy 47mm AT gun knocked out three tanks,38 and continuous heavy AT fire neutralized the efforts of the rest of the armored support. Company F, like Company I, was able to reach its objective but equally unable to maintain its hold in the face of fierce enemy fire. Heavy casualties, coupled with the loss of tank support, made it doubtful that the assault platoons could hold against an enemy counterattack, and Lieutenant Colonel Magee ordered his men to withdraw. Company G furnished fire and smoke cover to the embattled unit, and by 1630 Company F had evacuated its casualties and drawn back to its jump-off positions where it was relieved by Company E.39

The enemy forces defending the gorge and ridges of the Awacha Pocket, the 23d Independent Infantry and 14th Independent Machine Gun Battalions,40 held the 5th Marines to small gains during 6 May despite an intensive four-battalion artillery attack preparation41 and the call missions fired by NGF and air. The 1st and 3d Battalions blasted and burned out caves and bunkers that had held up their advance the previous day with the help of relays of gun and flame tanks.42 On the regimental left flank 2/5, which beat off a heavy counterattack at dawn, fought its way down the division boundary to link its lines with the 307th Infantry. By noon the battalion held an L-shaped front with all three companies on line, Companies G and F holding 450 yards along the division boundary and Company E joining its front with that of 1/5. The Army’s advance on the left flank made it possible for 2/5 to concentrate its fire on the enemy reverse slope positions that were holding up the rest of the regiment.

The lead message entered in the 1st Division G-3 Journal for 7 May was a commendation from General Hodge for the Marines’ work while under his command.43 During six days of desperate action the division had suffered 1,409 battle casualties, including 199 men killed in action and died of wounds, while securing the north bank of the Asa Kawa and the outer defenses of Dakeshi. At 0600 General Geiger officially assumed control of the 1st Marine Division zone of action and of the IIIAC artillery battalions that had been attached to XXIV Corps.44 The 27th Infantry Division’s artillery remained in position to reinforce the fires of Marine artillery in support of the III Corps attack.

Heavy rains on the morning of 7 May delayed the projected IIIAC advance until tanks were able to negotiate the muddy terrain. In the 1st Marines’ zone, the new regimental commander, Colonel Arthur T. Mason,45 ordered 3/1 to support the attack of the 2d Battalion on Hill 60 with all available weapons by firing into the enemy reverse slope defenses. All morning long the regiment’s mortars concentrated on the enemy position, and at 1400 when tanks finally reached the front lines the battalion attacked with Company E in assault.

Artillery fire covered the foot of the objective while mortars and assault guns blanketed the crest and reverse slopes. The company swept to the top of Hill 60 by 1422 in a vivid demonstration of “the effect of properly massed, supporting

CONICAL HILL, eastern anchor of the Shuri defenses, looms in the background of this shot of the 96th Division’s zone of advance. (Army Photograph)

fires in front of assault troops.”46 Once the company entered the impact zone, however, and supporting fires were shifted to other targets the enemy defenders emerged from their caves and engaged the Marines in hand grenade duels. Gradually the volume of Japanese fire of all types “grew noticeably stronger and progressively more intense so that it was evident that the enemy was receiving large reinforcements.”47 The threat of a strong counterattack measured against the dwindling strength of Company E forced Lieutenant Colonel Magee to adjudge the company’s advanced position untenable and to order a withdrawal to the previous night’s lines.48

The deep draw that cut across the front of 1/5 and the right of 2/5’s positions was the heart of the enemy’s Awacha defenses. At 0900 on 7 May, General del Valle and Colonel Griebel met with Lieutenant Colonels Shelburne and Benedict and their staffs to discuss methods of reducing the deeply dug-in Japanese positions that rimmed the draw and studded its steep slopes.49 An extensive preparation by artillery, rockets, and air was planned, and a reinforced company of tanks was moved up in time to support the infantry when it jumped off at 1200.50 In the center of the regiment’s line, 1/5 methodically worked its way forward 300-400 yards to the edge of the draw while 3/5 and 2/5, aided by Company L of 3/7 which moved into the line on the 1st Battalion’s

right,51 maintained flanking pressure with small local advances. The day’s progress was marked by intense close-quarter fighting with flame-thrower and demolition teams burning out and sealing enemy cave defenses. Although the gains made by 1/5 indicated the 62d Division’s hold on the Awacha Pocket was slipping, the fury of opposition met gave no grounds for undue optimism.

The 77th Infantry Division, advancing through the same type of terrain that confronted the 1st Marine Division, garnered 400-500 yards of enemy territory on 7 May against increasingly stiffer resistance. The Japanese had completed the reorganization of their defenses after the disastrous 4-5 May counterattack and were well dug in to block the most direct route to Shuri. The 305th Infantry (less 2/305 at Kerama Retto), relieved of its garrison duties on Ie Shima by 27th Division units, moved into the 77th Division’s line to replace the 307th Infantry and gave General Bruce a fresh regiment for use in the proposed Tenth Army attack.

Fresh troops were being readied behind the rest of the XXIV Corps front as the 96th Infantry Division, which had absorbed 4,000 replacements, terminated its rehabilitation and training activities and prepared to replace the 7th Division along the east coast. The 7th’s assault regiments, the 17th and 184th Infantry, did not passively await relief, however, but drove ahead on 7 May to take Gaja Ridge and inch their way into the tangled network of defenses that guarded the western approaches to Conical Hill.

A cold, driving rain began to fall late in the afternoon of 7 May and continued through the night and the next day, immobilizing tank support along the entire Tenth Army front. The 17th Infantry, still hammering at the enemy ridge positions south of Kochi, fought an infantryman’s battle where gains were measured in Japanese dead rather than yards of ground seized. The lack of effective cover and the loss of tank support on 8 May prevented the 184th Infantry from gaining ground in the flatlands along the coast and held its advances to limited objectives in the foothills of the broken inland plateau near Kibara. During the day the 96th Infantry Division moved into assembly areas in the rear of the 7th’s lines in preparation for relief operations.

Along the rest of the Tenth Army front on 8 May the rain effectively cancelled out planned offensive operations. Assault units mopped up in the vicinity of their night positions and sent patrols forward to spot enemy dispositions. In the 1st Division zone 75mm pack howitzers from 1/11 were manhandled into the front line in an unsuccessful effort to place direct fire on enemy emplacements.52 During the morning the news of the victory in Europe was spread through the infantry units, drawing a universally apathetic reaction53 from rain-soaked men whose immediate future was tied irrevocably to the battle plans of a deadly enemy in positions scant yards from their own. Exactly at 1200 every available artillery piece and naval gun fired three volleys at vital enemy targets to apprise the Japanese of the defeat of their Axis partner.

The 22d Marines, which General Shepherd had selected to lead the 6th Division’s attack in southern Okinawa, moved out from Chibana on 8 May, and by 1530 2/22 and 3/22 had relieved 2/7 on its lines along the Asa Kawa. At 1600 the 6th Division commander assumed responsibility for his zone of the corps front.

The 22d Marines began their offensive action

against the Japanese at daybreak on 9 May when patrols from Companies I and K of 3/22 were dispatched to reconnoiter the Asa Kawa and the ruined bridge that spanned it. The patrols reported that the bridge was impassable to foot and motorized traffic, that the depth of water in the estuary at high tide in its shallowest point was four feet, and that the river bed was mud. At noon the same companies sent out other patrols to find suitable crossing sites and to determine the strength and dispositions of the enemy.54

The Company I patrol crossed upstream and drew fire from positions along the river bank, but it noted that other caves and pillboxes farther south seemed unoccupied. Company K’s patrol, which waded across the river at its mouth, met sufficient opposition to force it to withdraw, and its report included the finding that the soft river bed would not support a tank ford.

The 2d Battalion, in position near Uchima, also patrolled to its front during the day. Although no enemy activity was noted by Company E, which sent men out to the left flank and front, a Company G patrol that crossed the Asa Kawa promptly drew heavy fire. The patrol was able to rescue the pilot and observer of an artillery spotting plane which was shot down over enemy territory before it disengaged itself and withdrew. From the information gathered by all the patrols the division and regiment were able to formulate a workable plan for crossing the river and seizing a bridgehead which could be effectively exploited.

The 6th Engineer Battalion was ordered to move light bridging material up to the 22d Marines’ area prepared to lay a footbridge across the estuary near the ruined bridge site after darkness. The 3d Battalion with 1/22 in support was to cross the river at 0300 on 10 May, secure the bank, and be ready to attack south at dawn. The 2d Battalion was to establish a strong point on high ground southwest of Uchima from which it could support the attack of 3/22 and 1/22.55

The plans of the 6th Marine Division to breach the Asa Kawa line were part of the over-all preparations for the Tenth Army attack. On 9 May Tenth Army Operation Order 8-45, which set the date of the attack for 11 May, was put into effect by dispatch. The immediate army objective was the envelopment and destruction of the enemy forces occupying the Shuri defenses and the ultimate mission was the total defeat of the Japanese Thirty-second Army.

The 1st Marine Division made substantial advances on 9 May which materially aided in straightening the division line. The division attack was first called off because of the muddy condition of the ground but then rescheduled for 1200 as it became evident that tanks would be able to furnish support to assault troops.

Colonel Mason decided to commit his 1st Battalion to crack the Hill 60 defenses. During the two days 1/1 had been in regimental reserve it had reorganized and absorbed 116 replacements to fill partially the gaps left by the 259 casualties it had suffered between 30 April and 6 May. The battalion moved into positions behind 2/1 and at 1205, following an artillery preparation, jumped off with Company C in assault to seize the finger ridge that commanded the eastern slopes of Hill 60. By 1240 Company C was partially on its objective, and as resistance stiffened Company B was sent in on its right. The success of 1/1 in penetrating the high ground east of Hill 60 enabled Colonel Mason to put into effect the next stage of his attack plan, and he ordered 2/1 under cover of fire from 3/1 to advance and seize Hill 60.56

Company E with tanks and assault guns in direct support moved rapidly to the crest of its objective. By 1400 it had full control of the hill and its reverse slope, and engineers were busy blowing the numerous cave entrances.57 Resistance to 1/1’s advance continued to mount and assault companies suffered heavy casualties, especially from fire coming from their left front. As a result there was a general shift to the left as Company C moved into the 5th Marines’ zone to wipe out the opposition, and Lieutenant Colonel Murray committed Company A on the right of Company B to close the gap to

AWACHA POCKET, showing the gorge which was the scene of much bitter fighting by the 5th Marines.

2/1’s lines on Hill 60. Exhaustion, crippling casualties, and lack of contact almost stopped the attack, but it was renewed at 1600, and the battalion battled its way through 150 more yards of broken terrain and stubborn resistance to reach its initial objective and tie in with Company I of 3/5 on the left and E of 2/1 on the right.

Late in the afternoon Lieutenant Colonel Murray, who had come up to the front to supervise the disposition and defense preparations of his companies, was wounded by a sniper. Before he was evacuated Murray designated Captain Francis D. Rineer, commanding Company B, as temporary battalion commander, and Rineer conducted 1/1’s night defense until he was relieved the following morning by Lieutenant Colonel Richard P. Ross, Jr., regimental executive officer.58

Company K of 3/7 which had been acting as reserve for 3/5 reverted to parent control on 9 May and moved into the front line on the right of Company L so that 3/7 had two companies in assault for the 5th Marines’ attack. The battalions facing the Awacha Draw, 1/5 and 2/5 were directed to furnish supporting fire for the attack of 3/7 and 3/5 on the rugged ground at the mouth of the draw. At 1200, after an air, NGF, artillery, and mortar preparation, the assault battalions jumped off.

Initial progress was rapid, and the advance reached its first objective, the same ridge line faced by 1/1, before the volume of enemy fire from 3/7’s exposed left flank forced a halt. At 1515 it was necessary to commit 1/7 (Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley), which had moved up from the Gusukuma during the morning, to close the gap that had opened between 3/7 and 1/5.59

New division orders were issued during the afternoon of 9 May to meet the problem raised by the bitter defense of the Awacha Pocket and the absolute necessity of continuing the division attack to the south in order to reach Tenth Army objectives. The 5th Marines (less 3/5) was assigned a limited zone of action on the left of the division front and given the mission of reducing the Awacha defenses. The 7th Marines (with 3/5 attached) and the 1st Marines were given new boundaries that placed them across the division front in position to jump-off for the 11 May attack.60 At 1855 Colonel Snedeker relieved Colonel Griebel of responsibility for the new 7th Marines’ zone and took control of the front lines of 3/5, 3/7, and 1/7 in preparation for a division attack the following morning.

The decision to concentrate the 5th Marines’ efforts on the Awacha Pocket was welcomed by the 77th Division since its right flank had suffered galling fire from the enemy defenses there. On 9 May this division, using tactics it was to employ throughout its drive toward Shuri, concentrated its offensive effort on one small sector of its front. All available supporting fire was delivered against the limited ridge line objective of 3/305 in the center of the division zone. After the assault battalion had gained a hold on the ridge, it was in a position to deliver flanking fire on similar objectives in front of other elements of the division. This system of advancing by seizing salients in the enemy line was the most effective that could have been employed by the 77th, which faced an interminable series of hills and ridges whose main axis was generally perpendicular to its direction of advance.

The 17th Infantry, which had fought doggedly to secure Kochi Ridge and the high ground to the west of Conical Hill was relieved by the 382d Infantry of the 96th Division on 9 May. At the same time the 383d Infantry moved to forward assembly areas behind the 184th, and on 10 May it relieved the 184th on its lines directly north of Conical Hill. Both fresh regiments were able to destroy enemy strong points that had held up the battle-weary 7th Division’s advance and improve the positions of their division for the 11 May offensive by seizing key hills that guarded the approaches to Conical. General Bradley assumed command of the east coast sector from General Arnold at 1420 after the last front line unit of the 184th Infantry was relieved.

The 77th Division continued to improve its jump-off position on 10 May and concentrated its offensive effort in the zone of 3/305 which seized additional high ground that led toward the key road junction north of Shuri. The 306th Infantry again supported the 305th’s attack and in addition fired across the division boundary into the reverse slopes of the hill positions in front of the 382d. Progress for the 77th Division in the area southwest of Maeda had been steady since 5 May, but the enemy was now ready with a reorganized and reinforced 32d Regiment and the dug-in tanks and 90mm field guns of the 27th Tank Regiment to dispute any further movement down the main highway that led to Shuri.61

The readjustment and reinforcement of enemy lines necessary after the 4-5 May counterattack had been completed by 10 May. Remnants of the 62d Division that had fought the 77th Infantry and 1st Marine Divisions in the tangled ridge network between Maeda and the Asa Kawa were being gradually withdrawn toward Shuri to be rebuilt to some slight semblance of their former strength with drafts from the Boeitai, Naval Base Force, and service and supply troops. The 24th Division, whose main reinforcements at this stage of the battle were taken from former sea raiding base battalions and division troops, held the front from Dakeshi to Gaja with the 22d and89th Regiments facing the U.S. 96th Division.

The 44th IMB with the full strength 15th IMR as a nucleus and strong reinforcements from the3d Battalion, 2d Infantry Unit, 7th Independent Antitank Battalion, 1st and 2d Independent Battalions, and the 26th Shipping Engineer Regiment faced IIIAC. Although the 3d Battalion, 2d Infantry Unit had been committed at Dakeshi, the main strength of the brigade was screened from the Marines by outposts and scattered strong defensive positions

MARINES of Company B, 1/7 cautiously advance toward the smoking slopes of Dakeshi Ridge on 10 May.

still held by units of the 62d Division. Once the 6th Marine Division crossed the Asa Kawa, however, and the 1st Division reached Dakeshi Ridge, IIIAC would be deeply unmeshed in the Japanese brigade’s highly organized defensive position.

During the night of 9-10 May 1/5 repulsed two counterattacks and turned back numerous enemy infiltrators in fighting that sometimes closed to bayonet range. In the morning more than 60 enemy bodies were counted in front of the battalion’s lines. Lieutenant Colonel Shelburne issued his attack order at 0600 after the excitement died down, and at 0800 the battalion moved out in a column of companies with Company A in the lead. A swift advance of 400 yards reached the corps boundary, and Company C was committed on the left of A to deepen the battalion front.

Tanks, which had been scheduled to move up in support, were blocked from joining the assault companies by lack of a suitable approach route. About 0845 heavy machine-gun and mortar fire coming from the front, both flanks, and the rear pinned down the battalion in its advanced position and casualties skyrocketed. It was impossible to evacuate the wounded by carrying parties, and amphibious tanks, which were called up to do the job, were unable to negotiate the rugged terrain. Finally at 1700 Shelburne requested a heavy smoke barrage and ordered his men to withdraw under its cover and bring back their casualties. By 1945, 1/5 was back in the lines it had held the evening before.62

Despite the fact that 1/5 was repulsed in its attempt to isolate the Awacha Pocket, the 5th Marines made significant gains against the enemy position on 10 May. Lieutenant Colonel Benedict, using 12 gun and three flame tanks with his infantry fire teams, was able to overcome all effective enemy resistance in that part of the Awacha Draw which lay in 2/5’s zone of action. Streams of flame were played over the northern slope of the draw while tanks working in relays blasted enemy positions in front of 2/5 and 1/5. Company G, accompanying the tank firing line, moved into the draw and cut down the enemy troops flushed out of caves by the armored flame throwers. Companies E and F then advanced in their sectors to and through the draw, mopping up the enemy as they went. By nightfall 2/5 had broken into the heart of the Awacha defenses, but there were still many pockets of desperate resistance to be accounted for.

In the 7th Marines’ zone of action, the 3d Battalion on the right was pinned down on its line of departure by accurate shelling from artillery and mortars. Heavy small-arms fire from caves and pillboxes to its front prevented any appreciable advance during the day. As a result 1/7, which paralleled the advance of 1/5, attacked at 0800 with an open flank. Initial progress was rapid against scattered opposition, and at 0842 Lieutenant Colonel Gormley committed Company A on the left of the assault company (B) to strengthen his front. Mortar and machine-gun fire from Dakeshi Ridge increased steadily during the morning despite artillery and 81mm mortar concentrations laid on the ridge and village.

At 1145 enemy machine guns firing from a draw in the 5th Marines’ zone on the rear of Company B effectively slowed the advance. A smoke barrage by 81mm mortars and the mopup efforts of Company G of 2/7 failed to eliminate fire from the draw, and Gormley was forced to order a halt. When 1/5 began its withdrawal at 1700, 1/7 came under direct fire from three sides and its left rear and gradually was driven from its forward positions. At 1754 Gormley gave permission for all his assault units to pull back to their original lines.63

The road leading out of the west end of Dakeshi was the objective of the 1st Marines’ attack on 10 May. The 3d Battalion jumped off at 0800, advanced swiftly to the railroad cut which bisected the regimental sector, and held up awaiting the attack of 1/1. The tanks which were to support the 1st Battalion had been delayed by a 6th Division tank which struck a mine and blocked the only tank road into 1/1’s area. At 1020, the tanks having arrived, both battalions resumed the attack, advanced steadily, and reached the low ridge that overlooked the Dakeshi road. All attempts by the assault companies, K and L of 3/1 and A and B of 1/1, to move beyond the road were ineffective. Vicious enfilade fire from Dakeshi Ridge drove back all combat patrols and made it evident that the ridge would have to be taken before any further advance to the south could be made. During the day, Company I of 3/5 kept pace with the attack of 1/1 and at nightfall linked the lines of the 1st and 7th Marines.64

Shortly after dark on 9 May engineers began construction of a footbridge across the Asa Kawa in front of 3/22, using the approaches of the old bridge. At 0300 Company K, followed closely by Company I, began crossing the footbridge, and shortly thereafter Company A of 1/22 started wading the shallow eastern portion of the stream. At about 0530 two Japanese “human demolition charges” rushed out of hiding and threw themselves on the south end of the footbridge, destroying it.65 The possible loss of the bridge had been provided for in attack plans, and engineer demolition parties with the assault troops breached the sea wall to provide direct access to the front lines by LVT’s loaded with supplies and reinforcements.

At daybreak the assault companies of 3/22 attacked to the south. Company K, moving along the coast in broken terrain, was pinned down immediately by enemy fire from all sides. In the center, Company I was able to advance slowly with the aid of covering fire from Company A. At 0900 Lieutenant Colonel Donohoo

ordered Company L to cross the river and support the attack. Artillery and supporting ships fired continuously to clear the path for the infantry but could not bring their fire in close enough to the front lines to destroy the enemy emplacements. The situation called for the direct fire of tanks, but the tanks were unable to ford the Asa Kawa despite repeated attempts.66

The stubbornness of the enemy resistance led Colonel Schneider to order 1/22 to attack and relieve the pressure on the 3d Battalion. Companies B and C moved up on either flank of Company A and assaulted the first of a series of ridge positions southeast of Asa at 1345.67Supporting fire from the left flank was delivered from the 2/22 strong point established by Company G at 0730.68 The regimental advance continued along the entire front during the afternoon despite heavy rifle and machine-gun fire, with the longest advances being made in the center of the line by 1/22. At dusk the attack was halted and the assault companies dug in with firm control of a bridgehead 1,400 yards long and 350 yards deep. At 2200 the 6th Engineer Battalion began erecting a Bailey bridge to enable tanks to cross the Asa Kawa and support the 22d Marines in the Tenth Army attack of 11 May.

Tenth Army Attacks69

The Japanese furnished the prelude to the Tenth Army attack of 11 May. At 0630 combat air patrols intercepted the first of a series of enemy raiders that attempted to reach the Ie Shima and Hagushi anchorages during the morning. Kamikazes crashed and seriously damaged a Dutch merchantman, the Tjisdane, and the destroyers Evans and Hadley, while a bomb crippled LCS 88. The Hadley was credited with shooting down 19 planes and the Evans with 15 out of a total of 93 credited to ship’s AA and defending air patrols.70

Naval gunfire assignments of five battleships, six cruisers, and 13 destroyers71 to support the army’s attack were not affected by the enemy air raid. Planes from TF 58, TF 51, and TAF were constantly on station to fly strike missions and augment the fire support of artillery and NGF. The attack got off on time at 0700 all along the front, and assault troops advanced slowly against bitter resistance.

Tanks and self-propelled guns were not available to the 22d Marines at the start of its attack. Intermittent shelling by enemy artillery during the night had slowed engineer progress in the construction of a Bailey bridge across the Asa Kawa. With daylight enemy observers on the Shuri heights were able to see the engineer working parties, and the tempo and accuracy of the shellfire increased. The time set for the completion of the bridging operation was successively delayed from 0400 to 0600 to 1000, and the first tanks actually crossed the river at 1103.72

During the morning close-in support for the infantry was limited to the 75mm howitzers of the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion firing into the seaward face of the cliffs on the right flank of 3/22. Lieutenant Colonel Donohoo sent Company K into this area to clean out its caves and pillboxes while Companies I and L moved up the coastal road to outflank the 147-foot hill northeast of Amike that dominated his zone of action. Intense enemy fire from the steep and rocky hillside raked the open ground along the road and pinned down the assault troops. At 1150 Company B of the 6th

Tank Battalion moved into position to support the infantry, and the attack was renewed. Enemy AT guns registered hits on three tanks, destroying one, before the tanks were able to silence the fire.73 By midafternoon 3/22 was fighting its way up the hill in a close quarter battle with the enemy defenders, and at 1600 after an 800-yard advance the battalion reported that it had established control of the high ground which overlooked Naha.74 General Shepherd, who had observed 3/22’s attack from the 22d Marines’ observation post, sent Lieutenant Colonel Donohoo a message commending “every officer and man who participated in this assault for his personal bravery and the fine team work exercised by all units in capturing this precipitous and strongly defended terrain feature.”75

The fire from the tanks of Company B that supported 3/22 also aided the advance of the 1st Battalion in the center of the regimental zone of action. Extremely heavy small-arms fire coming from a coral ridge that overlooked the left flank of the bridgehead had driven back 1/22’s assault company (C) during the morning’s attack. The direct fire of the NGF support ships assigned to IIIAC was laid on the objective, and the 6th Division sent several urgent messages to corps requesting assignment of flame-throwing tanks to sear the caves and covered positions that infested the upper reaches of the ridge.76

Four of the armored flame throwers were detached from the 1st Division, but they did not arrive in time to support the attack which was renewed when the Shermans of Company C, 6th Tank Battalion reported to 1/22. Heavy fire from the ridge halted the first tank-infantry assault. However, when the tanks with 3/22 were directed to cover the reverse slopes with fire while those of Company C hit the forward face, the infantry was able to advance swiftly and seize the objective.77 Portable flame throwers and satchel charges were used to silence the defenders in rugged close-in fighting

ATTACKING under enemy fire, men of 1/22 race through the ruins of the sugar mill south of the Asa Kawa.

for what proved to be an extensive headquarters and supply installation.

The main effort of the 22d Marines’ attack had been made by 1/22 and 3/22. The 2d Battalion’s mission was to advance and seize a hill that paralleled the general line of objectives facing the other battalions and to maintain contact with 1/22 and the 1st Division. The battalions on both flanks were pinned down almost immediately after the morning’s attack began, but Company G in assault for 2/22 was able to maintain its initial steady momentum against moderate opposition. Rather than hold up his men to keep contact, Lieutenant Colonel Woodhouse committed Companies E and F on the left and right flanks respectively to link up the front lines. Advances on both flanks later in the day served to straighten the line, and the battalion dug in on its objective at 1700.78

The banks of the railroad cut that ran down the division boundary furnished 2/1 with a covered route of advance on 11 May. The battalion’s objective was the high ground west of Wana, but attempts to attack through 1/1’s lines on the approaches to Dakeshi Ridge were stopped by accurate machine-gun fire from its

6TH DIVISION ZONE OF ACTION on 11 May showing tanks moving across the Asa Kawa in the foreground.

reverse slopes and the forward slopes of Wana Ridge. Company E on the left was pinned down, but Company F, moving down the railroad cut, made steady progress toward the objective. By 1300 Lieutenant Colonel Magee found it necessary to commit Company G in column behind F to back the attack and keep contact. Tanks, which deployed to silence opposition from Dakeshi Ridge, drew heavy artillery and mortar fire on Company E’s area.79 At 1600, when Company F was partially on its objective and holding up so that 2/22 could tie in, Company G was caught in a terrific artillery bombardment which caused casualties to mount alarmingly. All available artillery and air was concentrated on suspected enemy gun positions to free Companies G and E, but finally it was necessary to order the companies to dig in where they stood.80 A gap which had opened between 2/1 and the 7th Marines during the day was closed by the 3d Battalion which took cover from the persistent artillery fire81 by occupying the east bank of the railroad cut.

In addition to providing close-in fire support, the tanks working with the 7th Marines on 11 May also evacuated the wounded; some were

WHITE PHOSPHORUS SHELLS screen the advance of the 5th Marines on 11 May.

taken up through the escape hatches and others rode out on the back of the tanks which provided an armored shield between stretcher cases and enemy fire.82 The need for tank protection to evacuate the wounded was indicative of the fury of opposition met by 1/7 and 2/7 which carried the brunt of the regiment’s attack. Both battalions advanced about 800 yards during the day, converging in front of 3/7 in a double envelopment of the enemy position and gaining a firm hold on Dakeshi Ridge.

Company F, in assault for 2/7 on the right, worked some elements over the crest of the ridge and into the outskirts of Dakeshi village by 0948, but the intensity of enemy fire from coral caves and pillboxes on the reverse slopes mounted as the men penetrated into the core of defenses. Further progress was impossible, and the rest of the day was spent in mopping-up action along the ridge to consolidate the battalion’s hold.83The same heavy fire from reverse slope defenses met Company C of 1/7 when it reached the top of the ridge at 1116, and Lieutenant Colonel Gormley sent Company A forward early in the afternoon to strengthen the line and fill in on the left toward the division boundary. Both companies used tank fire, flame throwers, grenades, and demolitions to seal the caves and emplacements that infested the newly-won ground and finally gained a secure hold on the objective.84

The last organized resistance in the Awacha Pocket was eliminated on 11 May by 2/5, while

Map 27

1st Marine Division

Captures Dakeshi Ridge

1/5 moved up behind 1/7 and wiped out bypassed enemy strong points. At nightfall the 1st Battalion linked the positions of the 7th Marines and 305th Infantry to provide a solid front line along the division boundary. The 2d Battalion made contact with 2/307 which had moved up to support positions behind the 305th Infantry during the day.

Assault battalions in the 77th Division’s zone of action gained 400-500 yards during the 11 May attack. The broken nature of the terrain that guarded the approaches to Shuri gave the enemy ample opportunity to take the flanks and at times the rear of advancing troops under telling fire. The progress of 1/305 on the division right “was won inch by inch against fanatical resistance from enemy strongpoints,”85 and flame-throwing tanks were used extensively to burn out the defenders. The 3d Battalion of the 306th Infantry, advancing along the division’s left boundary, made slow progress, and attempts by 2/306 to turn the enemy flanks were halted by withering fire. The division consolidated its gains at sundown and dug in under sporadic mortar and artillery bombardment.

A company-sized counterattack hit 1/382 on the right of the 96th Division during the night of 10-11 May, and the battalion was still engaged in a heavy fire fight at the 0700 jump-off hour. It was not until 0930 that tank-infantry teams were able to advance around the flank of the last stubbornly resisting enemy pockets. Because of mounting casualties and critical ammunition shortages, the battalion, after gaining over 400 yards during the day, was forced to withdraw from its advanced positions on the forward slopes of the next objective, 400-foot-high Dick Hill. The same murderous machine-gun cross-fire and mortar bombardment that thinned the ranks of the 1st Battalion kept 3/382 from making any appreciable gains during its attack on the ridges northwest of Kuhazu. The 383d Infantry on the left of the division front made substantial progress on 11 May with the 1st and 2d Battalions battling their way forward 600 yards to a firm hold on the northwest slope of Conical Hill.

The following day’s attack netted few yards for the 383d but enabled the assault battalions to consolidate their positions on Conical Hill’s forward slopes and wipe out enemy resistance in the vicinity of the front lines. Advance elements of 1/382 again reached Dick Hill and again were driven back by a veritable wall of enemy fire despite flank support from 2/306 and 3/382. The division’s lines were straightened during the day when 3/382 advanced 400 yards to seize high ground that brought it abreast of 1/382 and 1/383.

The 306th Infantry’s mission in the 77th Division’s 12 May attack was to furnish fire support to flanking units. While elements of the 2d Battalion worked with 1/382, the 1st Battalion concentrated its mortars and machine guns on the reverse slopes of hills and ridges facing the 305th Infantry. Attacking into a maze of heavily defended hills, ravines, and gullies, the regiment advanced 400-500 yards to gain the crest of one ridge only to be confronted with killing fire from the next. Mopping up in the rear of the assault battalions, 2/307 shifted its positions 300 yards to the south in order to maintain contact with the 305th and protect the division right flank.

The 400-yard gap along Dakeshi Ridge between the night positions of the 1st and 2d Battalions, 7th Marines was closed on 12 May. The 2d Battalion with Companies E and F in assault, E on the left, cleaned out the reverse slopes of the ridge with the aid of gun and flame tanks. Carrier strikes were called down on targets directly in front of Company E as it moved into the ruins of Dakeshi. The hail of mortar and artillery fire which had been falling intermittently since the start of the Tenth Army attack, increased sharply in intensity as the enemy attempted to stop the battalion’s forward progress. Company F, moving along a spur of Dakeshi Ridge toward the regimental boundary, was hit especially hard by mortar concentrations and was found to have a total strength of 93 at the end of the day’s action.86 At 1522 Company E made contact with Company C of 1/7 on the ridge above Dakeshi, and both battalions consolidated their hold for the night along the northern outskirts of the village and on the high ground on its flanks. (See Map 27)

Company C of 1/7 repulsed a determined counterattack at 0235, driving off the enemy who left 65 known dead in front of the battalion’s lines, 30 of whom were credited to artillery defensive fires. At 0737 orders were received from Colonel Snedeker to mop up Dakeshi Ridge, advance to an objective line just beyond the village, and support the advance of 2/7 by fire. Company A moved out in assault at 0821 and meeting no opposition, walked into Dakeshi at 0912, while Company C cleaned out cave positions on the ridge. By 1330 the battalion had reached its objective line, and Company B had been committed to the left rear of A to back up the forward positions. Resistance to the day’s advance on the left of the regimental front was erratic, but it stiffened as night fell and reconnaissance indicated that the ground directly north of Wana Ridge was strongly organized in depth.87

The attack of the 1st Marines to improve its positions west of Wana was held up for three hours until 2/1 could be resupplied by air with rations, ammunition, water, and medical supplies. Heavy and accurate shelling and small-arms fire covered the whole battalion area, causing mounting casualties and forcing Lieutenant Colonel Magee to consolidate the remnants of Companies E and G under the Company G commander in order to obtain an effective striking force.

At 1030 these companies attacked in an attempt to come abreast of Company F’s forward positions. Every step of the way was contested by swarming enemy snipers and heavy machine-gun fire from the vicinity of Wana. Japanese artillery and mortar observers on the heights to the left front had perfect observation of the battalion’s routes of supply and evacuation. Under these circumstances, gains by the depleted companies were negligible, and most assault elements were pinned down almost as soon as they moved out. As dusk approached the companies were forced to dig in where they stood, at best only a few score yards forward of their 11 May positions.88

The 3d Battalion, attacking on the left of 2/1 with Companies K and L in assault, was forced to pull up short of the eastern extension of the ridge line along which the 2d Battalion was strung out. Partially protected by the cover along the banks of the southern tributary of the Asa Kawa, 3/1 was able to advance 300 yards to the southeast toward Wana Draw before the volume of enemy fire forced a halt. At 2230, after the troops had dug in, Company L reported that it was undergoing a counterattack by an unestimated number of enemy troops. Division alerted the 5th Marines at 2300 to be prepared to support the 1st against the counterattack, but 3/1 was able to drive off the Japanese without the aid of reinforcements.89

The 6th Division front on 12 May began to assume the shape it was to hold throughout most of the month’s fighting. The formidable enemy position at Wana, 1,000 yards to the northeast of the 6th Division’s lines, effectively blocked the advance of the 1st Division. Consequently, the left flank units of the 6th Division were open to observation and direct fire from the western slopes of the Shuri massif and were unable to match the advances made by troops moving down the west coast toward Naha.

On the second day of the Tenth Army attack, the 22d Marines concentrated its efforts in the center of the line where opposition from enemy hidden in caves and tombs was steady and heavy. The 1st Battalion, with a company of tanks in support and Companies A and B in assault, advanced steadily and seized its objective line, the high ground north of the Asato Gawa, by 1400. On the right of the division front, 3/22, from its advanced positions secured the previous day, reached the commanding ground at 0920 and sent patrols through the suburbs of Naha to the river where they found the bridge demolished and the river bottom muddy and unfordable. Both battalions dug in for the night with their lines on the northern outskirts of the Naha suburbs.90