Royal Naval Rating Seaman Bill Baker

By Dan Cavanaugh

Curiosity guided me to retired Royal Naval Rating Seaman Bill Baker. We sat purely by chance across from each other in a quaint restaurant on a Jersey shore, with tables so close conversation seemed required. Slim and extremely fit for 81, his gray hair was combed neatly back, skin slightly wrinkled His blue eyes sparkled accenting his gray eyebrows. His British accent made listening quite easy. Somewhere he mentioned he’d been in the war, which was greeted with mixed reviews by his wife Winn. Clearly she’d heard it before. I hadn’t, and was interested to know why some 57 years later he still wanted to tell his story. Why was it so important after all these years? I listened intently. It seemed Great Britain entered the war in 1939 and Bill followed in March of 1941.

Curiosity guided me to retired Royal Naval Rating Seaman Bill Baker. We sat purely by chance across from each other in a quaint restaurant on a Jersey shore, with tables so close conversation seemed required. Slim and extremely fit for 81, his gray hair was combed neatly back, skin slightly wrinkled His blue eyes sparkled accenting his gray eyebrows. His British accent made listening quite easy. Somewhere he mentioned he’d been in the war, which was greeted with mixed reviews by his wife Winn. Clearly she’d heard it before. I hadn’t, and was interested to know why some 57 years later he still wanted to tell his story. Why was it so important after all these years? I listened intently. It seemed Great Britain entered the war in 1939 and Bill followed in March of 1941.

“I was quite a long way from my wife Winn in North Wales, Bill started. In the Royal Navy we always got all night leave, but on alternate nights. I would do my friend’s duty and he could pop off for two days and have time to get home and back again. The following weekend he would do the same for me. One weekend I went home to see Winn, and when I got back they had all been shipped out. The dormitory was empty, I was marched off to the cells and they were assigned to Singapore. For punishment I had to work 7 days without pay including in my spare time. There wasn’t any war on with Japan at the time. ‘All the lights are blazing there’ I was told. ‘That’s a peacetime assignment you missed’. In 1942 the Japanese invaded. All the guns were pointing out to sea and the Japanese came in by land and took Singapore. The prisoners were held in concentration camps. I don’t think any of them where ever heard of again.

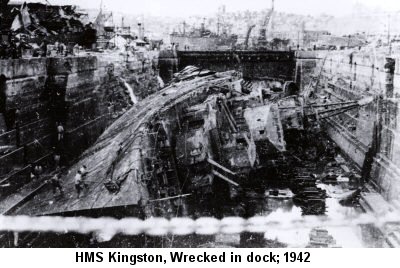

I was eventually assigned to the destroyer H.M.S. Kingston. On March 22, 1942 we left Alexandria without much trouble and were within about a day’s journey of Malta when Italian war ships came up. We chased them, and they ran away. But they were only lagging back leading us towards the Italian battleship Littorio, with it’s sixteen inch guns. Our ships had only 4 and 8 inch guns. This battleship was picking off the whole convoy from a vast distance. They ordered the destroyers to make a torpedo attack, cruise right up to the thing and launch torpedos, which hadn’t been attempted since World War I. We closed within torpedo range, and let one go. The next minute we had a shell come in high up from the Littorio. If it had hit the hull it would have blown us to smithereens, but it exploded above the upper deck and killed and blew the arms and legs of nearly everybody on the upper deck. I was on the upper deck, but fortunately I was on B gun on the bow of the ship. It and the bridge protected me from the explosion. The shells where popping on each side of us like someone trying to hit double top on the dart board. Luckily there were tremendous waves. We hit the Littorio with one torpedo and she turned and fled. We isolated one boiler and continued on to Malta.’

I was eventually assigned to the destroyer H.M.S. Kingston. On March 22, 1942 we left Alexandria without much trouble and were within about a day’s journey of Malta when Italian war ships came up. We chased them, and they ran away. But they were only lagging back leading us towards the Italian battleship Littorio, with it’s sixteen inch guns. Our ships had only 4 and 8 inch guns. This battleship was picking off the whole convoy from a vast distance. They ordered the destroyers to make a torpedo attack, cruise right up to the thing and launch torpedos, which hadn’t been attempted since World War I. We closed within torpedo range, and let one go. The next minute we had a shell come in high up from the Littorio. If it had hit the hull it would have blown us to smithereens, but it exploded above the upper deck and killed and blew the arms and legs of nearly everybody on the upper deck. I was on the upper deck, but fortunately I was on B gun on the bow of the ship. It and the bridge protected me from the explosion. The shells where popping on each side of us like someone trying to hit double top on the dart board. Luckily there were tremendous waves. We hit the Littorio with one torpedo and she turned and fled. We isolated one boiler and continued on to Malta.’

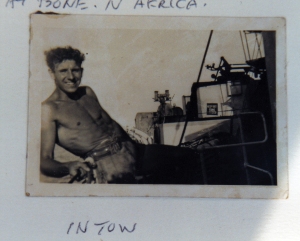

After the H.M.S. Kingston was sunk in dry dock in Malta I was assigned to the H.M.S. Badsworth. We escorted a convoy into this little port off Africa and were steaming up and down when all of the sudden we hit an acoustical mine, a mine that goes off by sound. We started to sink by the stern and had taken on so much water that little waves were running up and hitting the steam funnel. The engineer officer said ‘C’ Mon Baker we have to go below and see the damages.’ Baker wasn’t too thrilled. We went down into the mess deck and water was coming up and stuff was floating around. We shut the water tight door. On a destroyer you can’t go below deck from one end of the ship to the other because it’s all water tight compartments. We retreated to the next compartment, which was the petty officer’s mess deck. As the ship went up and down in this gentle swell, the compartment wall was going in and out like a tin can. Plink, plonk. Plink, plonk. The chief engineer officer said ‘Baker if that gives way we should go down. Get the engine room staff up here and we’ll shore it up with these big timbers.’ We got the big timbers, put them up against this partition, drove wedges in, and got it all shored up. We came up on deck and the whole ship was deserted, not a soul on board except the captain. It was like a ghost ship. A boat came out from the shore, and the Captain said to get the wounded in it, and all the seaman jumped on board. I don’t blame them. The only people who returned to Liverpool with the ship were the people who stayed on it. They only wanted the engine room staff and a few seaman anyway . After we got into Liverpool we had to rebuild the whole stern of the ship and I remained on as part of the skeleton crew. That was basically the end of the war for me. I was hitchhiking home on D-Day.”

After the H.M.S. Kingston was sunk in dry dock in Malta I was assigned to the H.M.S. Badsworth. We escorted a convoy into this little port off Africa and were steaming up and down when all of the sudden we hit an acoustical mine, a mine that goes off by sound. We started to sink by the stern and had taken on so much water that little waves were running up and hitting the steam funnel. The engineer officer said ‘C’ Mon Baker we have to go below and see the damages.’ Baker wasn’t too thrilled. We went down into the mess deck and water was coming up and stuff was floating around. We shut the water tight door. On a destroyer you can’t go below deck from one end of the ship to the other because it’s all water tight compartments. We retreated to the next compartment, which was the petty officer’s mess deck. As the ship went up and down in this gentle swell, the compartment wall was going in and out like a tin can. Plink, plonk. Plink, plonk. The chief engineer officer said ‘Baker if that gives way we should go down. Get the engine room staff up here and we’ll shore it up with these big timbers.’ We got the big timbers, put them up against this partition, drove wedges in, and got it all shored up. We came up on deck and the whole ship was deserted, not a soul on board except the captain. It was like a ghost ship. A boat came out from the shore, and the Captain said to get the wounded in it, and all the seaman jumped on board. I don’t blame them. The only people who returned to Liverpool with the ship were the people who stayed on it. They only wanted the engine room staff and a few seaman anyway . After we got into Liverpool we had to rebuild the whole stern of the ship and I remained on as part of the skeleton crew. That was basically the end of the war for me. I was hitchhiking home on D-Day.”

Bill Baker reminded me alot of my father. What seemed like good fortune to me, seemed ordinary to him. He was just doing what he thought was right. I was struck by the coincidence of my own good fortune. Maybe Bill had provided some clues as to why my father was one of the lucky ones who came back. These honest and ordinary men, acting in good faith had made such a difference. My heart swelled with immense gratitude, for all the ordinary guys who sacrificed many of the prime years of their youth, so I that I could experience mine.

Bill continued “The extraordinary thing is, I was in Italy a few years ago on a electric train going to Sarento. I got to talking to this nice old Italian guy standing next to me in a blue navy hat.”

‘I was in the Navy.’ I told him

‘I was in the Navy too.’ He replied

‘I thought he was talking about the merchant navy. What in the war?’ I asked

‘Oh yes!’ he replied.

‘What ship were you on?’ I continued.

‘The Battleship Littorio’ he replied

‘The Battleship Littorio?! On the 22nd of March?’ I asked

‘Oh yes!’

So then I told him my side of the story. When it was over we were practically in tears as we gave each other a hug.”

Our World War II Veterans

Our World War II Veterans